Letter from the PI: Introducing the ZooLink Suite of Projects

Letter from the PI: Introducing the ZooLink Suite of Projects

Prof. Eric Fèvre

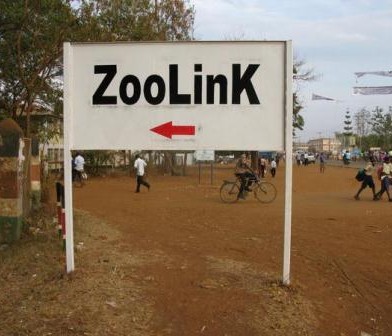

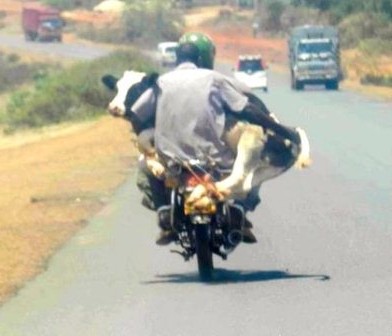

It’s a real pleasure to write the first “Letter from the PI” for the Zoonoses in Livestock in Kenya (ZooLinK) project, part of the Zoonoses in Emerging Livestock Systems programme, funded by the UK Research Councils (led by the BBSRC), UK DFID and UK DSTL.

Our project has been underway since 2015, engaged in planning and staffing, followed by refurbishing of our field lab and the commencement of field activities in Kenya. It’s satisfying, a year and a half in, to now be able to start reporting on how we are doing and what we are up to. While we have been and will continue to share updates through social media on a regular basis, our project newsletters serve to provide slightly more indepth ongoing reporting of our work. Newsletter articles will also appear on our project website as blog articles – we are active on social media both on the web at www.zoonotic-diseases.org and through twitter @ZoonoticDisease, with #zels #zoolink.

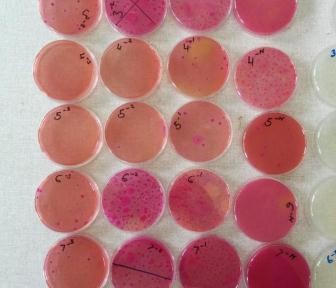

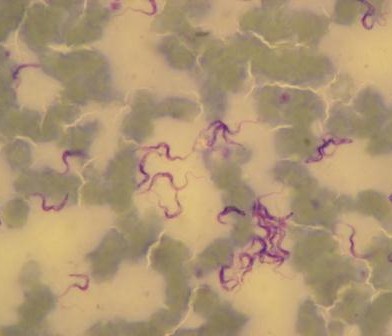

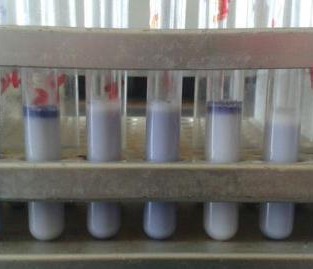

Dr. Laura Falzon has been appointed as our postdoctoral epidemiologist, leading activity in our field sites. Laura is co-ordinating scientific activity at our primary laboratory, based in the town of Busia, on Kenya’s border with Uganda. The lab houses BSL-2 standard biosecurity and is fully spec’ed for basic parasitological diagnostic work, serological assays, PCR and molecular diagnostics and microbiological assays. Later this year, we’ll have some exciting DNA sequencing capacity there too. Samples are flowing through this laboratory where a number of our project scientists are working, and two Masters theses have already resulted from this ongoing work (projects undertaken by Isaac Ngere and Maurice Omondi on arboviruses and Fasciola spp– see our blog). Dr. hristine Mosoti is our ZooLinK project manager, and is the primary point of contact for any external queries on the project.

While the ZELS programme does not directly fund PhD students, we’ve successfully attracted a real diversity of academic interests to our programme with some innovative co-funding mechanisms. Ten PhD students are currently active in the programme, some nearing the end of their first year, others just beginning their studies, on topics as wide ranging as within household economics to genetic diversity of parasites – we’ll ensure that the students’ work is highlighted regularly in the student’s section of this newsletter – see Jessica Floyd’s entry in this edition.

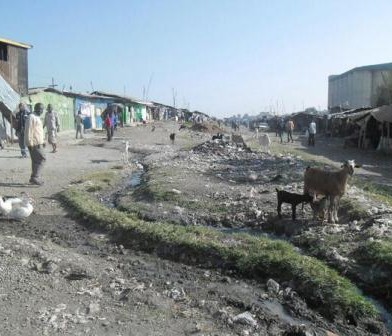

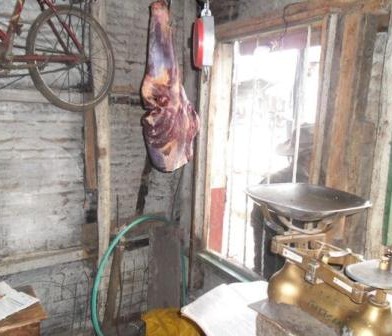

We’ve been engaging very successfully with the national veterinary system too, with two seconded members of County Veterinary Staff attached to our project and so far two cohorts of Animal Health Diploma holders coming through on 3 month “One Health” graduate internships. Elsewhere in Kenya, we’re investing, with our national partners, in the surveillance of several other zoonotic disease issues: we put significant effort into surveillance for Rift Valley Fever during the rainy season early this year and in to understanding the epidemiology of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in camelids and humans. We’ve also been working on enumerating and vaccinating dogs for rabies in central Kenya. Much work, and many challenges lie ahead, but our excellent team is already proving that it can face these challenges successfully, and I am very proud of the excellent interdisciplinary work that we are doing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.