An account of the 11th TAWIRI conference featuring presentations from our team

An account of the 11th TAWIRI conference featuring presentations from our team

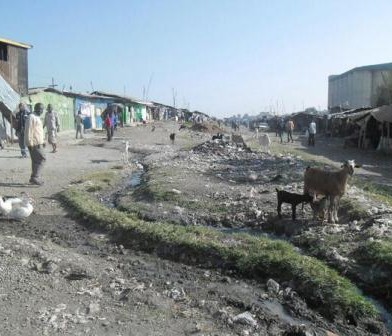

The eleventh Tanzania Wildlife Institute (TAWIRI) conference themed, “People, livestock, and climate change: Challenges for sustainable biodiversity conservation”, was held from 6th to 8th December 2017 at the Arusha International Conference Centre (Fig.1). The conference had over 300 local and global participants with diverse knowledge on wildlife conservation with 4 keynote papers, 3 symposia, and 7 parallel sessions amounting to 167 oral and 19 poster presentations whose findings are intended to contribute to wildlife conservation in Tanzania and the region.

Figure 1: 11th TAWIRI conference information banner

The opening speech by the guest of honour, Deputy Minister-Tanzania Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (Fig.2), noted that the ever-increasing demand for land is a concern to all of us and puts preservation of natural resources in limbo and that there’s a danger of forgetting the fundamental principle that natural resources are not invulnerable and will be vulnerable indefinitely. In this regard, he urged wildlife scientists to continue providing scientific information to the government, wildlife management authorities, conservation and management partners to help reduce anthropogenic impacts on nature as well as information that will help guide effective development and conservation strategies.

Figure 2: Opening speech session – Guest speaker (5th from the right among seated)

The conference was timely to address the current conservation challenges facing Tanzania characterised by an increasing trend of livestock that interact with wildlife within protected areas. It was reiterated that scientific information has been and should be the backbone of the country’s success story in wildlife conservation. Thus, more scientific information is needed and required on how to improve the livelihood of communities around protected areas by enhancing economic growth by preserving natural resources and mitigating climate change impacts for sustainable conservation of biodiversity.

A key message from the conference presentations, as noted by Prof Sinclair (Fig.3), was that both protected areas and human-based areas are necessary but neither is sufficient for conservation. All ecosystems change continuously and therefore static boundaries will not solve conservation problems since they cannot accommodate change. It was reiterated that what is applicable today would be obsolete in 100 years and therefore important to improve human-dominated landscapes to make them more suitable for biodiversity for the future of protected areas and the stability of human ecosystems.

Figure 3: Keynote address by Prof Anthony Sinclair on, “The future of conservation”

Two of our ZED Group members were involved in organizing and participating in one of the 11th TAWIRI conference symposium themed, “Wildlife Diseases and Ecosystem Health” in collaboration with the Wildlife Disease Association, Africa and the Middle East (WDA-AME) section.

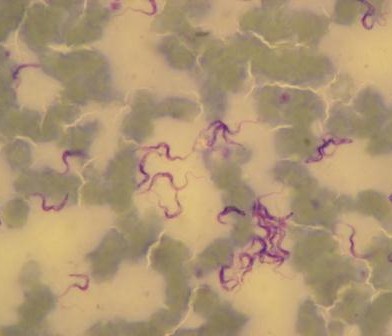

Dr Annie Cook (Fig.4) presented a collaborative work entitled, “a successful vaccine trial to control wildebeest-associated Malignant Catarrhal Fever in cattle.” The vaccine was noted to have an efficacy 92.2%.

Figure 4: Presentation on a successful vaccine trial to control wildebeest-associated Malignant Catarrhal Fever in cattle by Dr Annie Cook

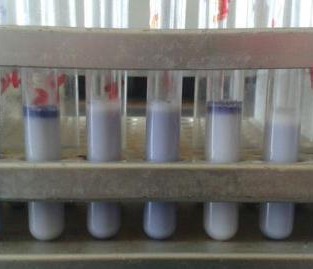

Dr Kelvin Momanyi (Fig.5) presented a collaborative work as part of the NEOH case study entitled, “Evaluation of the implementation of One Health in Kenya: A case study of the Zoonotic Disease Unit”. The presentation noted that the One Health office in Kenya (the Zoonotic Disease Unit) had performed moderately from the evaluation applying the NEOH One Health framework with a One Health Index of 0.73269.

Figure 5: Presentation on Evaluation of the implementation of One Health in Kenya by Dr Kelvin Momanyi

You must be logged in to post a comment.