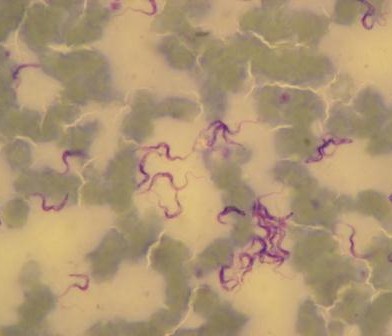

Research shows that six out of 10 emerging human infectious diseases are zoonoses. Thirteen zoonotic diseases sicken over 2 billion people and they kill 2.2 million each year, mostly in developing countries. Poor people are more exposed to zoonoses because of their greater contact with animals, less hygienic environments, lack of knowledge on hazards, and lack of access to healthcare. 80% of the burden of these zoonotic diseases thus falls on people in low and middle income countries.

A workshop at last week’s Uppsala Health Summit zoomed in on zoonotic diseases in livestock and ways to mitigate risk behaviour associated with their emergence and spread. Critical roles and behaviours of people and institutions in preventing, detecting and responding to zoonotic livestock diseases were identified – as well as necessary changes and incentives so we are well-prepared for infections long before they reach people.

These zoonotic infections often originate from livestock which can serve as a bridge for disease transmission between animals and humans. Thus, controlling zoonotic diseases in livestock is an important means to reduce infectious disease threats to humans. Zoonotic diseases are a threat not only to public health, but also to food production, food safety, animal welfare, and rural livelihood.

Within their own sectors, researchers and practitioners from different fields have a considerable understanding of outbreaks of disease and how to handle them. They also know they must bear in mind how local factors, traditions and politics can determine the outcome. But a disease outbreak causing deaths and disruption is always a complex picture. It requires all actors to gather knowledge from beyond their own field of expertise to be fully able to address disease outbreaks efficiently.

The 50 or so workshop participants, comprising vets and medics in a one health context, tackled two objectives. First, they identified who is involved in preventing, detecting and responding to zoonotic livestock diseases and the associated behaviours that need to change. Second, they set out some initial recommendations and incentives to mitigate risky behaviours.

Biosciences and behaviour

Co-organizer Ulf Magnusson from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences explained in his opening remarks that the challenge for the group lies at the intersection between biosciences and behaviour. We know a lot about the biosciences; but for the biosciences to be effective, we need to change and strengthen the behaviours of different actors involved in infectious diseases. He particularly emphasized the ‘one health’ element, that we need to look beyond animals to develop productive collaboration across the veterinary and medical professions.

Three people were charged to set the scene: Barbara Wieland from the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) introduced mainly Ethiopian experiences from rural settings; Eric Fèvre from the University of Liverpool and ILRI gave some urban perspectives from Kenya; and Elisabeth Lindahl-Rajala from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences shared a case on controlling Brucella in Tajikistan.

Wieland argued that effective prevention, detection and response requires good understanding of the specific ‘local’ situations in which livestock are kept and especially the roles of different people in this. Her research pointed to major gender differences with women closer to the animals, their care and feeding, and the farmstead and men more involved in marketing, slaughter and dealing with externals like vets. She also pointed to local cultural practices and their effect on handling and consumption of some animal-source products like milk or cheese. Taking account of these role differences and cultural aspects is very critical when designing interventions to tackle zoonotic infectious diseases. Focusing on the farmer actor, she identified especially the need for smaller more manageable changes, the transformative opportunities offered by information and communication technologies and the potential of one health to help overcome capacity and infrastructure problems in remote rural areas.

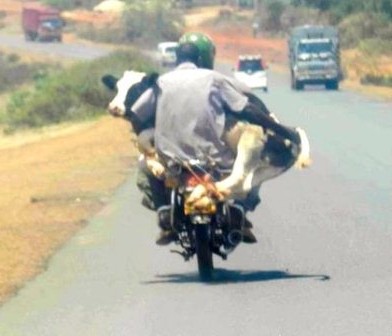

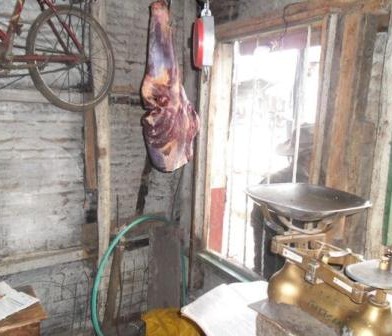

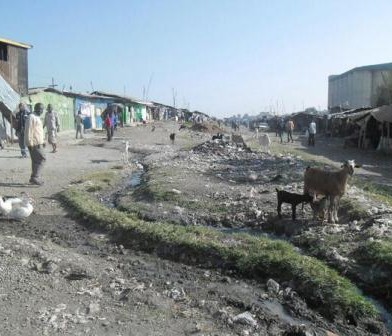

Fèvre reported on research in Nairobi to understand how pathogens from livestock are introduced and spread in urban environments. He introduced the notion of ‘interfaces’ – physical and social – as useful to help understand disease transmission between livestock and food systems, arguing that the behaviours of people, institutions and policies in and across these interfaces are critical in zoonotic disease spread. Looking at the food systems in a city like Nairobi, value chains connect the many different actors, moving animals and products, moving payments, moving animal health information, and ultimately also accelerating or hindering the spread of diseases. While Wieland focused on rural farmers as a primary actor, the urban systems and chains that Fèvre isolated comprise many different public and private actors, each with specialized roles and sets of desirable behaviours. Mapping and measuring these from a zoonotic perspective will allow current and future disease risks to be understood, leading to improved prevention, detection, and response.

You must be logged in to post a comment.