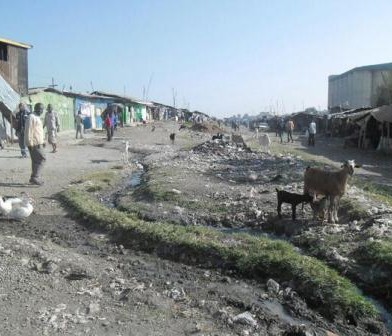

Our participation in the ZooLinK suite of projects will remain memorable. We have acquired sufficient knowledge and experience through the exposure given to us by ZooLinK staff and our participation in the target areas of the project. Since we joined the project on May 2018, we have rotated among the three functional units of the project, namely: (1) veterinary team who visit the livestock markets and slaughterhouses; (2) laboratory team and (3) clinicians team who visit the health centres. The following report will focus on the veterinary team. It describes the activities carried out therein and their relevance to the project.

Two of the interns working in the laboratory (foreground)

A normal ZooLinK day begins with packing the field car with the required consumables a day before the field. Such consumables include; red and purple topped vacutainers, nasal swabs, digital thermometer, heart girth measuring tape, ziplock bags, barcodes, consent forms, faecal pots, gloves, disinfectant, water, coveralls and gumboots etc.

“…our internship has equipped us with adequate disease surveillance skills in the animal field that will help us to extend the knowledge of disease control to farmers…”

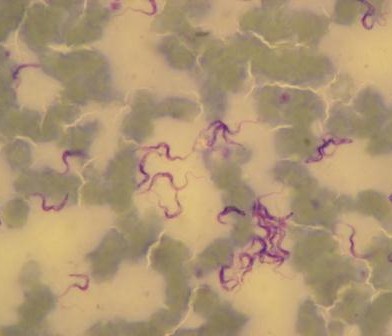

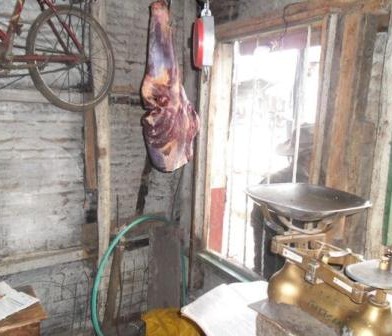

In the field, the veterinary team splits into two groups; one group works at the livestock markets and the other at the slaughterhouse. Upon arrival, at the livestock market, the animal is randomly selected and the owner identified to seek consent for sampling the animal and to answer a few questions. If he/she agrees, he/she signs two consent forms one of which goes with the animal owner while the other one remains for ZooLinK records. Before sampling, the animal is humanely restrained to ensure the safety of the animal, handler and person collecting the samples. Physical examination begins before the actual sample collection. Which entails checking for any abnormal discharges from the mouth, eyes, genitals and nose. On the skin swellings and injuries are recorded when present. Nature of the ocular mucous membranes is assessed and recorded, the mouth is checked for any lesions and sores as well the ageing is done from the dentition. The pre-scapula lymph nodes are palpated on both sides to ascertain any enlargement. Lifting of the loose skin of the neck is done to test for skin elasticity. The body condition of the animal is cored in a scale of 1-5. The fleece condition is recorded as either rough or normal and a tape measure used to measure the heart-girth to estimate the weight of the animal. The temperature is taken per-rectal. After the physical examination, the actual collection of the samples begins. Blood is collected from the jugular vein into a red top vacutainer (plain blood) for serology and an EDTA-purple top vacutainer (uncoagulated blood) for parasitology and hematology.

One of the AHITI interns sampling blood from a sheep

Nasal swabs are used to collect swabs from the nose. Nasal swabs are later cultured in the lab and used to test for the presence of Staphylococcus aureus. Fresh faeces are collected per-rectal and placed into a faecal pot. The faecal sample is cultured in the lab to determine the presence of E. coli, Salmonella and Campylobacter. External parasites like ticks, lice etc. are also collected if encountered. The same procedure takes place in the slaughterhouses but in addition, post-motem lesions like cysts, flukes, are recorded and collected inclusive of mesenteric lymph nodes from the pigs.

We are glad to declare that our internship has equipped us with adequate disease surveillance skills in the animal field that will help us to extend the knowledge of disease control to farmers and other stakeholders back at home.

You must be logged in to post a comment.