Co PI’s Letter: Planning and Policy Thread

Co PI’s Letter: Planning and Policy Thread

Prof. Julio D. Davila

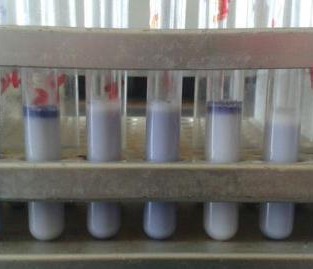

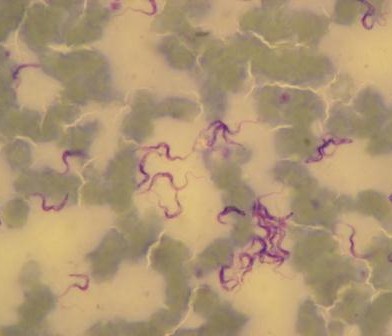

Our projects policy team aims to examine the links between social-environmental and spatial conditions and the microbial diversity that people are exposed to in urban and peri-urban areas. It also seeks to outline the institutional and planning context in which zoonotic diseases develop in Nairobi, and how this is shaped by spatial fragmentation.

In cooperation with Slums Dweller International-Kenya and APHRC, the Team previously collected data through a variety of means, including co-producing knowledge with local communities. In partnership with IIED, we have produced working papers, conference papers and policy briefs to showcase the results, with some currently being submitted to journals. Under the guidance of Prof. Muki Haklay and Dr. Sohel Ahmed, UCL post-graduate student Maayan Ashkenazi wrote a fascinating MRes dissertation on the different livestock keeping strategies by women in the low-income settlement of Mathare. She found that these not only vary according to the women’s economic abilities but along multi-scalar social and social characteristics arising from living in different villages within Mathare.

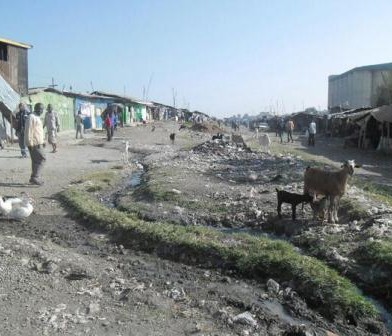

In our work we have also sought to build on the decade-long efforts of APHRC in gathering a rich array of primary information on health in informal settlements. We also found that not much attention has been paid in the literature to the planning, policy and structural issues that would appear to play a significant role in reproducing and entrenching endemic pathogenic environmental conditions, conditions that make disease (including zoonoses) prevalent in these settlements. Part of our work has involved outlining the institutions, actors, norms, practices, interactions, their (in) adequacy and complexities around the provision of infrastructure (water, sanitation and solid waste management) that promotes and perpetuates such pathogenic conditions in many parts of Nairobi. We have also sought to examine how legal, policy and institutional realities have influenced urban and peri-urban land use in Nairobi, and how such practices and interventions help shape livestock keeping and farming activities.

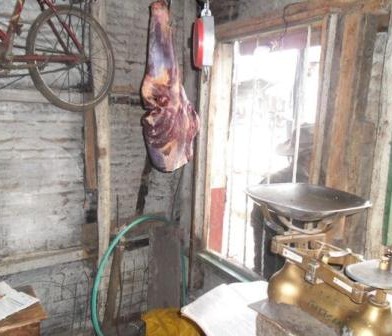

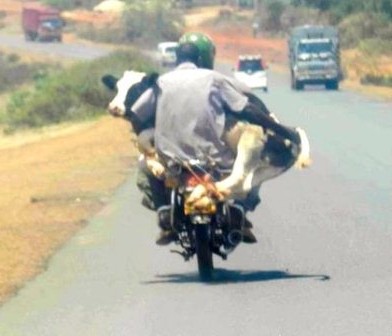

To that effect, earlier this year Dr. Sohel Ahmed conducted a series of interviews with research scholars, planners and policy makers in Nairobi. The results suggest that urban and peri-urban agriculture, including livestock keeping, are still not considered a legitimate urban land use neither in the Nairobi Master Plan and land-use maps, nor in the daily practice of local government officials. As a result of antagonistic views towards pro-poor informal farming from planners and other powerful actors, we argue that urban agriculture, particularly livestock keeping in Nairobi and its periphery, is unlikely to survive the effects of the rapid increases in land prices seen in Nairobi in recent years. This is partly the result of a lack of reliable investment alternatives, but also the result of inadequate or non-existent land-value capture mechanisms and an effective regulatory framework that guides growth and allows price increases to be re-invested in much needed infrastructure that benefits the city as a whole. Rapid urbanisation is accompanied by continued land speculation, rapid appearance of multi-storey buildings and conversion of large tracks of agricultural land to urban uses. As tracts of land become sub-divided into smaller plots, there is an observable shift to zero-grazing forms of livestock keeping (e.g. poultry). Hence, livestock and their material flows (i.e. meat, dairy and poultry) are continuously moving further away from central Nairobi.

Despite the 2010 constitutional reform allowing Nairobi County to prepare its own plan and control development under an ‘integrated development planning’ framework, in reality the County has little say over where new infra-structure, particularly electricity and roads, should be located. Water, roads and electricity are controlled by para-statals, thus taking away from the County government the power to decide on crucial components of its current and future growth. The County’s chronic institutional and resource deficiencies mean that the city will continue to allocate resources in such a way that mostly benefits a minority of residents, thus entrenching an east-west socio-economic divide. The inadequate and unsafe provision of water, sanitation and solid waste management has severe public health consequences for residents of poorer areas. Poor infrastructure places some people and their livestock at increasing risk of communicable diseases, and helps reproduce the conditions leading to chronic expo-sure to higher microbial diversity.

Julio D Dávila is Professor of Urban Policy and International Development, and Director of the Development Planning Unit, University College London.

You must be logged in to post a comment.