Multi-Institutional Collaboration at its best

Multi-Institutional Collaboration at its best

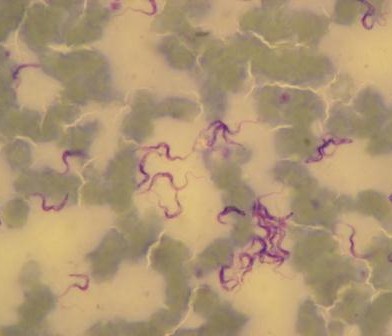

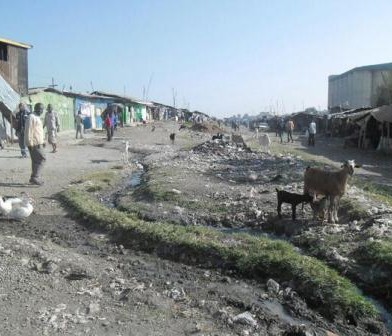

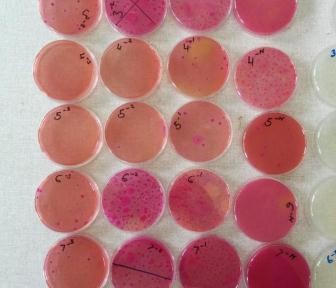

The Epidemiology Ecology and Social-Economics of Disease emergence in Nairobi (ESEI) project has hosted a variety of studies each with different study designs since its conception. MSc students, Mercy Gichuyia, James Macharia and I had the opportunity to work within an aspect of this wider project which involved a cross-sectional study among livestock keeping house-holds in Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements of Nairobi. We sampled blood and faeces from humans and different livestock species kept in the area and from the faecal samples, identified the prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Salmonella, Campylobacter and E.coli. This article will focus on the interaction with the different team members and partners during our field sample collection. The science we undertook is currently being prepared for publication.

MSc Students, James Macharia Mercy Gichuyia and Maurine Chepkwony

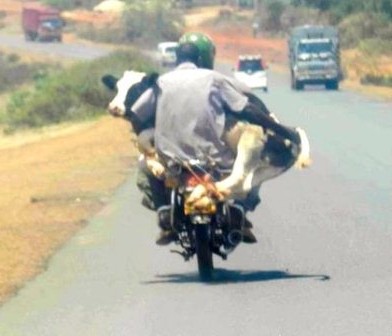

I had the opportunity to work with a large and robust multi-institutional team that was well coordinated and that gave me the best introduction anyone could hope for in how a collaborative project functions. Our typical field day began at 6am where we would be picked from the University of Nairobi, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences by Fredrick Amanya, Lorren Alumasa or James Akoko (all from ILRI). Our voyage would get us to the heart of the informal settlements where we would meet with a team from the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC): Sophie and Jacky, as well as three residents from each area who acted as our security guides and who are known to the chief, elders and the APHRC. These two groups of people were crucial in creating rapport with the households as well as locating the randomly selected households and also acted as guides while navigating the otherwise complex neighbour-hoods.

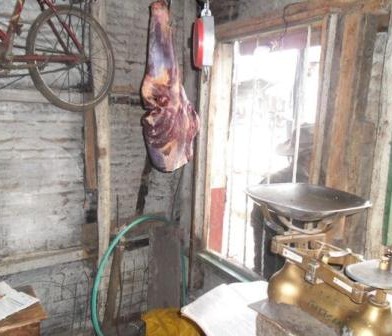

Lorren and Amanya (both Clinical officers based at ILRI) would give clinical feedback to household members whose laboratory findings required some form of clinical feedback. This acted as community feedback, one of the many community benefits from the project. After a morning of questionnaire administration, collecting human feacal samples (with the help of Fredrick and Lorren) and livestock sampling with the help of Akoko (project field coordinator), we (Mercy, Macharia and I) would then head to the University of Nairobi (UoN) for laboratory isolation and analysis of the livestock samples while the human samples were transported to the KEMRI-CMR laboratory.

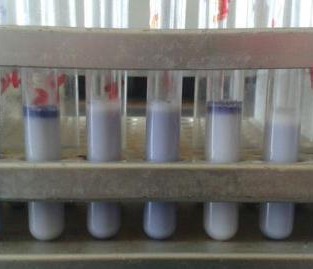

The fatigue from the morning physical work notwithstanding, laboratory work was very exciting owing to the very dedicated and motivating University of Nairobi Laboratory team led by Mr. Nduhiu Gitahi and comprising of Mr. Masinde, Mrs. Mungai, Ms. Wandia, Mrs. Gateri, Mr. Wambaru among others who offered us a lot of guidance and encouragement. The KEMRI –CMR laboratory team was also a huge part of our work and from my standing, a great resource to my work. I learnt several skills from this team particularly antimicrobial susceptibility testing using the agar dilution method from Mr. Ngetich and how to run a PCR as well as analysing of sequence data from Mr. Samuel Njoroge. The two institutional laboratories have very distinct tasks in the project, but the linkages of these activities and support from the Labora-tory coordinator, Dr. John Kiiru, gave me an excellent opportunity to accomplish different aspects of my project as a student since I was able to work in both laboratories with a lot of ease. The contribution of Dr. John Kiiru from KEMRI cannot be overstated especially in the facilitation of this inter-laboratory collaboration ob-served.

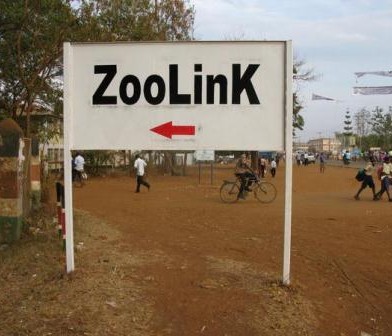

Now I understand that it takes a village to make a successful project. Even with the above mentioned activities, a lot went on in the background. The whole urban zoo team was very efficient in the coordinating of activities including field work, and laboratory equipment and reagent acquisitions. Dr. Victoria Kyallo and Mr. James Akoko were very effective, including Maurice Karani and Patrick Muinde (research technicians based at ILRI) were also instrumental in the project implementation. We were lucky to have supervisors: Prof. Kang’ethe (UoN) and Prof. Fevre (University of Liverpool/ILRI) who were always available and ready to support and guide us whenever we needed assistance in solving problems. I also interacted with Dr. Gemma Wattret from the University of Liverpool who was of great assistance in my Campylobacter research and especially so, in the molecular analysis and Laura Made of University of Liverpool in the study design. I cannot forget Dr. Annie Cook who taught us the ropes of rodent trapping and handling.

Although this article reports on a successful multi institutional interaction during my experience in the urban zoo project, it is actually an acknowledgement from Mercy, Macharia and myself to the project and, institutions and all the individuals mentioned and not mentioned in this article that were involved in making our Master of Science research projects a success. Working with the urban zoo team was without a doubt a very exciting experience as well as an opportunity for growth both personally and profession-ally. We are very grateful for all your input.

This article has been written by Maurine Chepkwony (An MSc student under the Urban Zoo Project, based jointly between University of Nairobi and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Kenya).

Under the

Under the

Human, food and environmental data are among the wide range of data collected within the

Human, food and environmental data are among the wide range of data collected within the

You must be logged in to post a comment.