Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) in pigs in Busia, Nairobi and Malawi

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) in pigs in Busia, Nairobi and Malawi

This blog post was authored by Catherine Wilson an MRES Student from the University of Liverpool attached under our #ZooLink project

I am investigating the prevalence of Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) in pigs in both Kenya and Malawi in extensive, low input production systems. The aim is to determine whether invasive NTS are present in the pig population of three study areas; one rural and one urban area in Kenya and one rural region of Malawi. In sub-Saharan Africa, NTS is a leading cause of human mortality, particularly in the very young, old, malnourished, or those suffering from co-morbidities such as HIV or malaria.

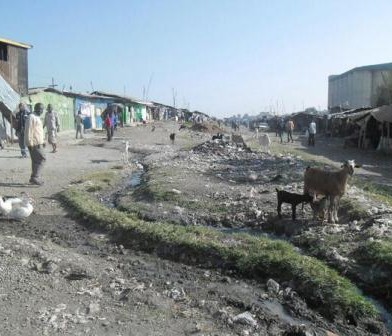

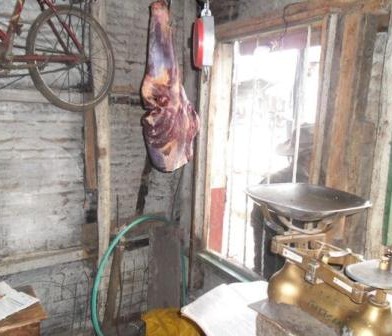

Pig slaughter slab in Bumala

An invasive NTS serovar has been found to be able to cause severe disease in chickens; suspicion is therefore arising that transmission between humans is not the sole route of spread of NTS, and that zoonotic transmission, especially from pigs, may have a role to play in the epidemiology of the disease. Should this invasive strain of bacteria be found in pigs, we will assess whether the same serovar clinically affects humans in the same geographical location, using data already gathered from human hospitals. A correlation between the two would indicate that zoonotic transmission may be occurring.

The final part of this study will assess the presence of drug resistance in the strains of NTS isolated from pigs, and whether this bears any correlation to a similar antimicrobial resistance pattern of NTS to that previously detected in humans in the same area. Should antimicrobial resistance be detected, other management techniques for the swine, such alterations in husbandry and hygiene, may be trialed. In the longer-term vaccination development may be a possibility as an important method of preventing zoonotic disease transmission in the study areas, for which research is currently in the very early stages.

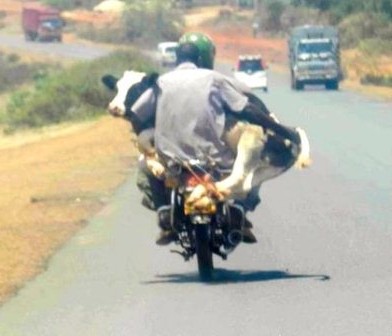

For sampling, both faecal and mesenteric lymph nodes samples were collected post mortem from 256 pigs in Busia and 304 pigs in Nairobi. The location in which the pigs were reared, as well as details of signalment, any previous antibiotic treatment if known and the method of transport of the pig to the slaughterhouse, were recorded for each individual pig.

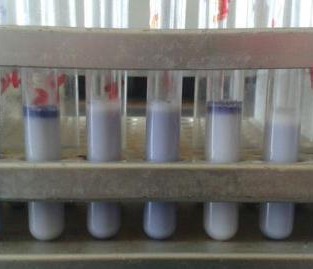

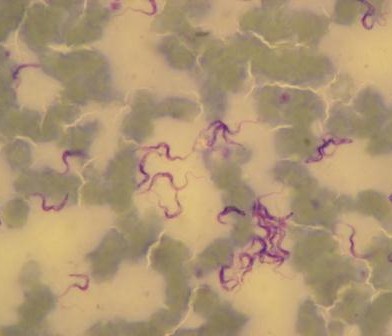

Samples were processed at the Busia Field Lab and ILRI laboratories respectively. Culture and serotyping was carried out to confirm the presence of Salmonella followed by antimicrobial susceptibility testing to a range of antibiotics. Positive isolates have then been stored for transport to the UK, where whole genome sequencing will be undertaken to identify the presence of any antimicrobial resistance genes. Once the results have returned, analysis is planned compare antimicrobial resistance profiles of the pig samples to those of humans in the same geographical location, to assess whether zoonotic transmission may be occurring.

You must be logged in to post a comment.