Zoonoses in Livestock in Kenya – The Beginnings of Surveillance

Zoonoses in Livestock in Kenya – The Beginnings of Surveillance

By Steven Kemp, PhD student, University of Liverpool

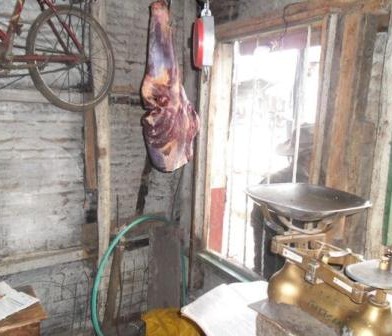

After a period of intense lab work at both KEMRI and the UK, investigating the patterns of antimicrobial resistance in faecal bacteria isolated from slaughterhouse workers in Busia County and the surrounding areas, I have returned to Kenya to begin the next phase of my PhD project.

ZooLinK is a cyclical programme which aims to set up surveillance systems of both human and animal health sectors over a long period of time. Surveillance of disease is particularly important, as the more information we have, the better we can treat diseases in both human and animal sectors. Recent research by colleagues indicates that the incidence of several zoonotic diseases, including E. coli, Salmonella sp. and others are vastly underestimated.

In recent times, we often hear about how we should now look to conform to the ‘One Health’ approach; this is where, in order to combat issues surrounding antimicrobial resistance and associated issues effectively, intersectoral approaches which share the cost and responsibility evenly between environmental, human & veterinary health professionals is required. In theory, this would be a perfect way to help educate and better promote antimicrobial stewardship.

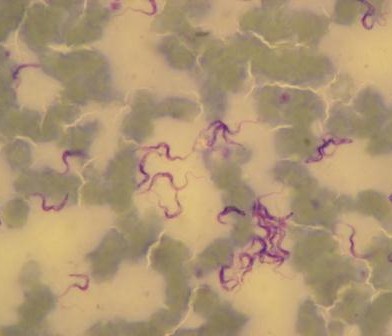

Currently, I have large amounts of data on access to, use of, and perceptions of antimicrobials from a variety of parties, including animal healthcare workers, district veterinary offices, farmers and agrovet shops. Over the last three months, I have added to this repository by investigating the amounts of antibiotic resistance found in E. coli, which have been isolated from the faeces of workers in 142 slaughterhouses which were selected in western Kenya. These included slaughterhouses in Busia County and the surrounding Kakamega and Bungoma counties.

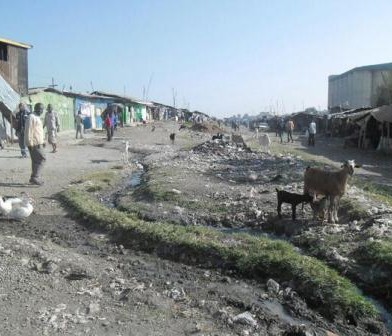

For the next portion of this study, I am attempting to collect four different sets of samples – to complete the ‘picture’. I will attempt to collect both human and animal faecal samples, from farmers and farm animals, water samples (to determine if there are patterns of resistance in animals which share common grazing grounds) and environmental samples (from the inside of homesteads, where animals are allowed to roam). By covering all of these bases, we will be able to eventually determine not only if there is transfer of antimicrobial resistance between animals and humans and the environment, but also which direction it is going in.

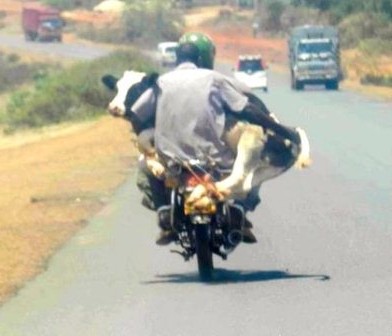

Typical small-holder farm in Funyula, Busia. Most farmers manage between 5-25 cattle.

Example of environment which may also be a good idea to sample in the future. If antimicrobial resistance can be found in the envi-ronment, then why not in wild animals such as these Zebra?

You must be logged in to post a comment.