In Summary

- During the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s fifth scientific conference, which also took place in February, scientists raised the alarm over the transmission of diseases from animal to humans.

- The World Health Organisation says that 60 per cent of the pathogens that cause infectious diseases in human beings come from animals.

- According to the US’s Centre for Disease Control and prevention, zoonoses include a wide range of diseases, ranging from mass killers such as anthrax, Ebola, swine flu, West Nile Virus, bird flu, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever and the Hendra Virus to subtle and slow killers like rabies, Rift Valley Fever and Brucellosis

During the funeral of a 39-year old woman who died of Aids in Homa Bay in February this year, a clinical officer who had attended to her engaged DN2 in a discussion about the Zika Virus in South America, and how it had triggered yet another debate on how man’s unguided relationship with nature is hurting him.

Sadly, neither the potential victims, nor the government, are adequately conversant of this to take the necessary precautions.

It is worth noting that at the time the Homa Bay funeral was taking place, across the Atlantic Ocean in Boston, US, the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) was also taking place. The discussion focused on yet another deadly infection that came to human beings from animals: Ebola.

In Kenya, the Ministry of Health allayed fears of possible disease outbreaks from the Ebola and Zika viruses.

Only a few scientists, like Lancet Laboratory’s executive officer, Dr Ahmed Kalebi, took note of the public health issues raised at CROI.

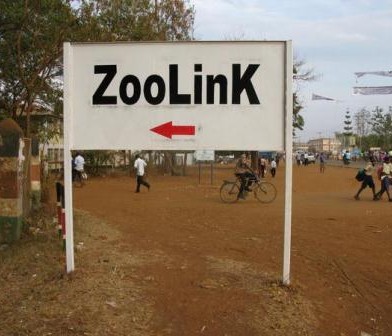

Meanwhile, during the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s (KEMRI) fifth scientific conference, which also took place in February, scientists raised the alarm over the transmission of diseases from animal to humans. They expressed concern about humans’ continued intrusion into wildlife territory.

Whether it is the burgeoning population or the desire to live in quiet, exclusive environments, human intrusion into animal habitats has grown considerably in the country in recent times.

The area around the Lewa Conservancy which straddles Meru and Laikipia counties, is a case in point. Apart from the herds of elephants and buffalos that roam the plains, one can also spot residential houses tucked away in between the trees.

A great deal has been documented about the booming real estate business in Laikipia County, which for decades was dominated by large territorial mammals such as rhinos, elephants and buffaloes.

Not surprisingly, this intrusion has seen elephants destroy crops in the areas neighbouring their habitat.

Now, experts are warning of a threat greater than the destruction of crops of trampling to death of humans: zoonoses.

Zoonoses are diseases transmitted from animals to humans.

The World Health Organisation, (WHO) says that 60 per cent of the pathogens that cause infectious diseases in human beings come from animals.

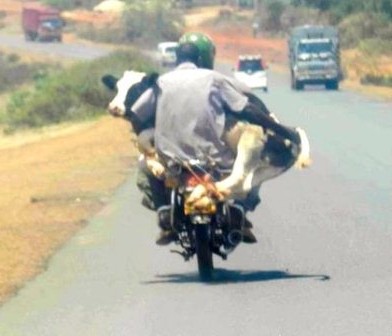

And researchers warn that the close interaction between humans and animals, whether wild or domesticated, is increasingly making Kenyans ill.

According to the US’s Centre for Disease Control and prevention, zoonoses include a wide range of diseases, ranging from mass killers such as anthrax, Ebola, swine flu, West Nile Virus, bird flu, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever and the Hendra Virus to subtle and slow killers like rabies, Rift Valley Fever and Brucellosis.

Although these diseases are a global health problem, their impact is felt more in Africa than in other parts of the world because they tend to be neglected. African governments dedicate few or no resources to detect and respond to them at the local or national levels. Only 0.7 per cent of these diseases affect people in developed countries as poor nations bear the brunt.

It was only after the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2013, which wreaked havoc in West Africa, that people started paying attention to the usually muted voice of researchers on the link between diseases, animals and the environment.

PUTTING UP SKYCRAPPERS

Given the rate at which construction is going on in the country, it is time we sat up and took notice.

Not too long ago, the ambience in Nairobi’s upmarket Kilimani allowed residents and colobus monkeys to live in harmony. Today, the gibbering of monkeys has been replaced by the roar of construction machines putting up skyscrapers.

The same trend can be observed in other parts of the country such as Lower and Upper Kabete, Gathiga, slightly past Kitisuru in Nairobi, Mang’u (Kiambu County), Kabarak and Sobea (Nakuru County) Nyahera (Kisumu County and Kapchorua in Nandi Hills (Nandi County).

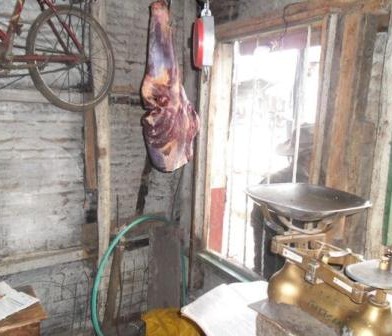

Unknown to many, as this trend continues, disease-causing pathogens are mutating, becoming more lethal and embedding themselves in the complex yet delicate human food chain and way of life.

A study in 2012 titled “Zoonoses: A potential Obstacle to the Growing Wildlife Industry of Namibia published in the journal, Infection Ecology and Epidemiology, drew a chilling pattern in Kenya, similar to Namibia’s cases of zoonoses: the serum of buffaloes in Ijara, Nakuru, Laikipia, Nairobi and parts of the North Rift tested positive for antibodies of Rift Valley Fever.

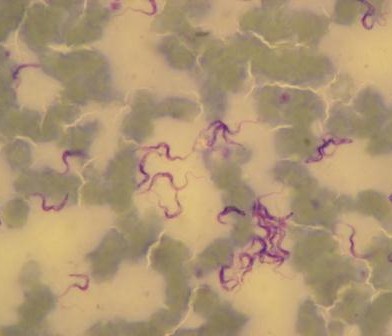

Dr Eric Osoro, a medical epidemiologist at the Zoonotic Diseases Unit (ZDU) in the Ministry of Health, says that at least 2,000 Kenyans die of rabies every year, which is unfortunate, given that it costs less than Sh100 to vaccinate a dog, compared with the thousands of shillings required to treat the viral disease.

“The number of rabies deaths reported is a gross underestimation of the actual number of deaths that occur in Kenya annually from this terrifying fatal disease,” he says.

Many more Kenyans could be dying of rabies, which can be caused even by a scratch by an unvaccinated dog, because the incubation period for the virus is estimated to be about two months.

“Sometimes the wound might have even healed, so none one would suspect it is rabies,” Dr Osoro says.

While rabies can be prevented by vaccinating dogs, WHO says it is 100 per cent fatal once the clinical signs appear.

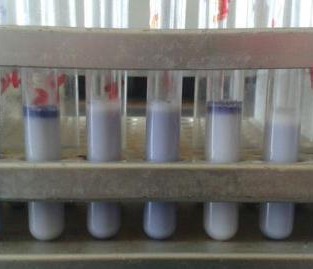

Apart from rabies, Dr Osoro also cautioned about Brucellosis — a disease one gets from taking milk that has not been boiled properly — and anthrax.

“Anthrax kills cattle in less than 12 hours, but many will consume the flesh because the animal looked healthy,” he says.

Prof Thumbi Mwangi, a clinical assistant professor at Washington State University in the US and a researcher on zoonoses at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), told DN2 that while the interaction between humans and animals is not necessarily a bad thing, failure to keep healthy animals increases the chances of ill health for humans.

PATHOGENS FIND NEW HOSTS

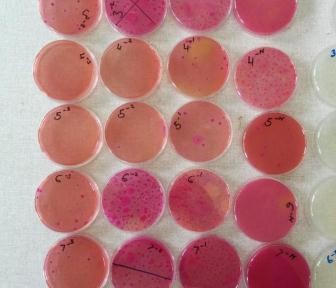

In March last year, Prof Mwangi carried out a study in which he tracked 1,500 households and their livestock in 10 villages in Western Kenya. He and his team obtained data on 6,400 adults and children, 8,000 cattle, 2,400 goats, 1,300 sheep and 18,000 chicken.

The results, published in the open journal, Plos One, revealed that for every 10 cases of animal illnesses or deaths that occurred, the probability of human sickness in the same household increased by about 31 per cent.

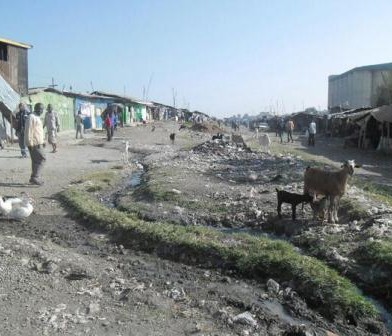

Prof Eric Fèvre, a professor of veterinary infectious diseases at the Institute of Infection and Global Health at the University of Liverpool and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), wrote a blog post, “Zoonoses in Africa” on the websitemicrobiologysociety.org, in which he said that urbanisation is presenting opportunities for pathogens to find new hosts to survive.

The post, published on November 11, 2015 read: “The intensification of farming, for example, leads to closer relationships between individuals and animals, generating opportunities for more rapid mutations as organisms move from host to host, while also providing a structured way for those pathogens to enter highly ordered food chains that branch out and reach very large numbers of people”.

Other studies paint an increasingly disturbing pattern of diseases either emerging, or the incidence of existing ones increasing.

A study in Dagoretti, Nairobi, by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), found that women were more exposed to cryptosporidiosis, a diarrhoeal disease transmitted from cattle to humans, because of their involvement in milking, feeding and watering the animals.

And a study by the Kenya Medical and Research Foundation (KEMRI) Kisumu and the US’ CDC linked a strain of tuberculosis to an area in Western Kenya where homes had a higher cattle:human ratio.

In wildlife settings, the situation is more complex. A 2014 study found cases of suspected rabies in Laikipia County where humans had encroached on animal habitat.

When landscapes and bio diversities are altered by activities relating to construction such as roads and farms, diseases are “created”: as trees are felled, the species that protect humans from the ones that act as disease-reservoirs are destroyed.

The harmful pathogens are usually multi-host, meaning they can live in many different animals, which gives them a competitive edge to survive as the protective trees are wiped out by human activity.

In 2012, ILRI reported that 2 million people are killed by zoonoses every year, thanks to the disruption of the ecosystem.

Malaria is a good example: as people in tropical countries like Kenya encroached on the habitat, the incidence of the disease quadrupled.

ECOLOGICAL BALANCE

When DN2 asked nine developers from Nakuru, Nairobi and Kisumu whether they consider the ecological balance of a location important when they are building, six responded with the question, “What is that?” After it was explained to them, all except one said they were “satisfied with the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) clearance”.

It is notable that NEMA officials and environmental inspectors have said at scientific forua that many of the constructions approved by the counties do not heed their counsel.

Only 1 per cent solution to wildlife viruses are known, according to WHO, and the ecology of diseases and wildlife immunology is in its infancy in Kenya.

Meanwhile, Kenya’s Zoonotic Disease Unit, has been lauded at various fora for its holistic approach, with its national rabies control strategy highly regarded.

It has conducted a large-scale study on the epidemiology of brucellosis, responded to many zoonotic disease outbreaks, and developed preparedness strategies for epidemic zoonoses such as Rift Valley fever.

Authored by James Akoko

Authored by James Akoko

Authored by

Authored by

You must be logged in to post a comment.