With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) about to expire, the global health community is looking back on major accomplishments in reducing poverty and improving health over the last 15 years. Perhaps one of the greatest surprises has been the success of international efforts to tackle neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

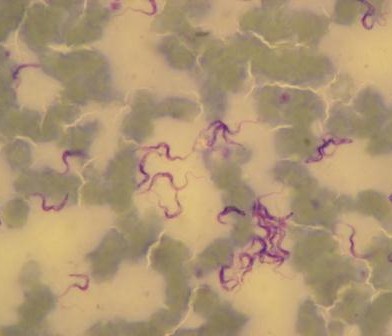

The World Health Organization estimates that nearly 1.8 billion people, including more than 800 million children, require annual treatment for NTDs. These parasitic and bacterial infections affect people for years or decades, mostly striking the world’s poorest, most marginalized communities.

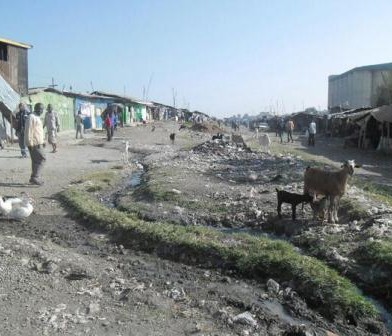

Adults and children living with chronic NTDs in Africa, Asia, and the Americas endure horrific disfigurement, blindness, and often extreme and debilitating pain. Children with NTDs often do not attend school, or have great difficulties learning in school, while adults cannot work. As a result, NTDs are leading causes of poverty in less developed nations. Yet, despite the scale of the NTD problem, just over 40 percent of those at risk receive the treatment they need.

Neglected tropical diseases fail to generate MDG interest

When the MDGs were created, NTDs were placed in a category of “other diseases.” To nobody’s surprise, this vague label did not generate much interest, compared to specifically named diseases like HIV/AIDS and malaria. In fact, AIDS and malaria stimulated multibillion-dollar initiatives for mass treatment and prevention, including the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the President’s Malaria Initiative and the Global Fund.

In response to the lack of interest, a group of committed investigators who have devoted their lives to research, treatment, and prevention of NTDs worked with the World Health Organization to target these diseases through mass drug administrations, using a package of pills that could be delivered annually for only 50 cents per person.

By 2006, USAID initiated an NTD Program that produced achievements as impressive as those of other bilateral and multilateral organizations. According to USAID’s statistics, this program has delivered more than one billion NTD treatments in 25 low- and middle-income countries over the last decade. This support is complemented by the UK Department for International Development’s (DFID) efforts, demonstrating a good case of donor harmonization.

By 2012, the average cost of treatment was reduced to 22 cents per person per year, by delivering treatment for many diseases at the same time. This freed more resources for distribution of the expanded drug donations that were pledged in the London Declaration on NTDs by 13 pharmaceutical companies.

Impressive gains in control and elimination

Following its Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) in 2013, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington released data for 301 diseases and conditions, and some of the numbers reflect impressive gains in NTD control and elimination. This progress is due in large part to USAID- and DFID-sponsored interventions. It includes a 39 percent decrease in the prevalence of trachoma and a 32 percent drop in lymphatic filariasis (LF). Impressive reductions in the prevalence of Ascaris roundworm (45 percent) and onchocerciasis, or river blindness (51 percent), have been achieved through other mass drug administrations.

But this is a modest reflection of the true impact of NTD programs. When researchers looked at age groups that tend to have the most infections, the decrease in trachoma and LF prevalence was even greater: 65 percent for trachoma and 53 percent for LF. The world is on track to achieve USAID’s objective of eliminating these diseases by 2020.

Thankfully, NTDs have been included in a number of critical inputs into the post-2015 development agenda process, including the High Level Panel report released in May 2013 and the Open Working Group (OWG) proposal for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) released in July 2014. The OWG reportincluded a specific target for NTDs, alongside AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

Choose the right indicator for SDGs

The next critical step for NTDs in the post-2015 process is to ensure that the right indicator is used to measure progress over the next 15 years. The NTD community strongly recommends the following indicator, as a global measurement tool: A 90 percent reduction in the number of people requiring interventions against NTDs by 2030.

In addition, we also need to consider the overlap between NTDs and other factors: nutrition; water, sanitation, and hygiene; maternal and child health; and education. Development goals cannot be achieved in isolation. In fact, NTDs are so inextricably linked to these development issues that their prevalence is seen as an effective proxy for broader socioeconomic and human development. The recently-published “worm index” demonstrates a high correlation between the prevalence of intestinal worms and development.

Finally, the SDGs need to incorporate a research and development agenda for NTDs, particularly for diseases not currently benefiting from major gains in mass treatment. This would include developing vaccines for hookworm infection, whose prevalence has decreased only five percent, and schistosomiasis, which has not decreased at all.

Hookworm vaccines are under development by our Sabin Vaccine Institute Product Development Partnership (Sabin PDP) in collaboration with the European HOOKVAC consortium, as is a vaccine for river blindness through The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa Initiative. Most likely, vaccines would be combined with mass drug administrations.

In addition, NTDs such as Chagas disease and leishmaniasis urgently require new interventions, including new drugs being developed by the Drugs for Neglected Disease Initiative, and the Sabin PDP’s therapeutic Chagas vaccine. Despite the lack of traditional market incentives to develop drugs for poor communities, the pharmaceutical industry has engaged in product development partnerships, and many have opened their compound libraries to academic and NGO partners.

Out of the spotlight, the NTD community has made significant strides. With explicit inclusion of these diseases in the SDGs, we can do even more. We have the opportunity to eliminate LF and trachoma before 2030, and reach key milestones in combating all NTDs through mass treatment efforts and the creation of new tools through research and development.

View this item also on the ILRI Livestock Matters online paper