Everybody needs to work together to address antibiotic resistance

Everybody needs to work together to address antibiotic resistance

This article was authored by Judy Bettridge. (Twitter @JudyBettridge)

There are many reports of patients putting doctors under pressure to dispense antibiotics, and this is clearly problematic. In many cases, antibiotics are simply not an appropriate treatment and will make no difference to the speed of recovery, especially for viral illness. With widespread media coverage and advertising, many patients are now better informed about the problems of antimicrobial resistance, and that taking unnecessary antibiotics can put them and their families at risk of future infections from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Doctors are the best-placed to know what is circulating in their local area, and can advise patients when their symptoms are most likely to arise from viral infections – and patients need to be ready to listen and take their advice. However, as my experience shows, doctors may also fall into the trap of anticipating patient expectations for antibiotics where no such pressure exists. Negotiation and understanding between doctor and patient is much more likely to result in satisfaction on both sides – and better compliance with any medication that is prescribed.

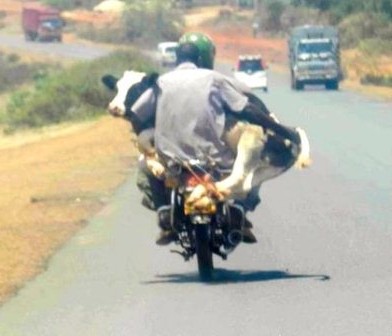

The very same issues arise in the veterinary profession, with vets and owners or farmers needing to discuss these complex decisions surrounding whether or not antibiotic use is appropriate on a case-by-case basis. Great progress has been made in many areas, especially in eliminating the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in Europe, but there is still much room for improvement. With so much information now available on the internet, it is not uncommon for people to come with very fixed ideas about what is wrong with their animal, and exactly what treatment they want. It is important to remember that many conditions that look the same can have very different causes. The bacteria in our bodies and our environment evolve and change over time, so that even two infections with identical symptoms may be caused by completely different bugs – which need a completely different antibiotic to treat them. For this reason, keeping and reusing antibiotics at a later date is never advisable –especially injectable drugs that can go off within a few weeks of opening. All antibiotics have an expiry date, and using less potent drugs to treat infections is another factor that can encourage antimicrobial resistance to develop.

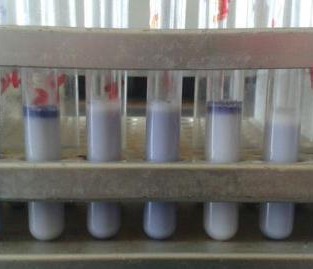

Always check the expiry date of drugs

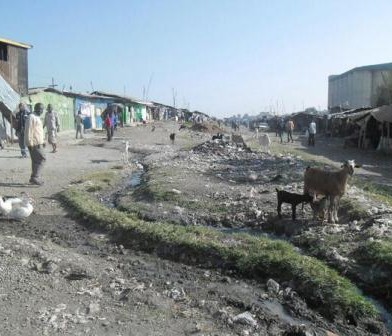

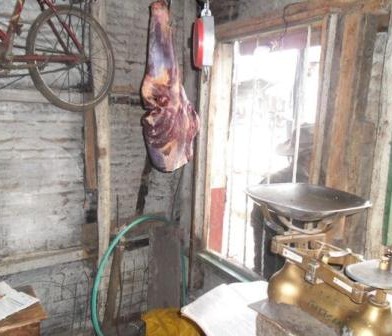

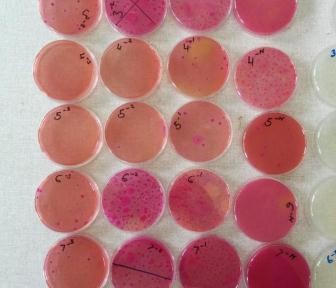

Where we work in East Africa, as in many other parts of the world, an additional problem is that antibiotic sales and use are frequently unregulated. A lot of commercial animal feed still contains antibiotics – so always check the label and ask the vet or seller if you are in any doubt. Good hygiene in animal production is much better as a preventative, as this can also help reduce viral and parasite infections that will not be helped by in-feed antibiotics in any case. If animals are sick, then involving a vet at an early stage is important to get the right treatment, rather than just buying a drug from an untrained seller and hoping for the best. Especially in remote rural areas, antibiotics may be on sale in the local kiosk, alongside the soap, candles and sweets. These are often human drugs, and so using them in animals is problematic – not only because they are not formulated to give the right dose for that species, but also because there are certain drugs that should simply not be used in animals. This may be because of dangerous residues that pass into the meat, eggs or milk, and so veterinary workers should always advise on how long to leave after treatment before animal products are safe to eat again. If they don’t offer this advice, along with clear instructions on how to use the drugs – ask! The other reason not to buy antibiotics from unqualified sellers is that there are some drugs that we want to preserve for use in only humans. These critically important antimicrobials are needed to treat difficult and often life-threatening infections in humans that don’t respond to other drugs. Some may be used by vets as a last resort, but their use should always be closely supervised.

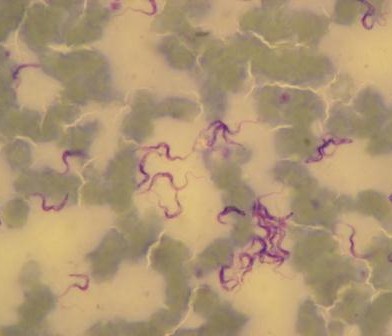

An antibiotic being administered to a cow

This is why this year’s theme for World Antibiotic Awareness week is “Seek advice from a qualified healthcare professional before taking antibiotics”. Wherever you are in the world, this is sound advice. Advances in science mean that rapid diagnostic tests are coming ever closer, and within a few years, genetic identification not only of the organism causing the infection but also what drugs it is likely to respond to will be possible. This will allow a diagnosis within a few hours, rather than days to weeks it can take with current laboratory methods. Accurate diagnosis, antibiotic selection tailored to every individual case and open discussions between the healthcare professional and the patient or carer as to whether antibiotic use is appropriate in every circumstance are all part of tackling antimicrobial resistance. Whether the healthcare professional is a doctor, nurse, veterinary professional or pharmacist, by making the most of their knowledge to help guide the decision to use antibiotics, everyone can play their part in helping to guard these precious resources for future generations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.