Endemic infectious diseases: the next 15 years

Endemic infectious diseases: the next 15 years

I have recently returned from the International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa. It was, as many have noted, a landmark event: a chance to celebrate the remarkable success of the HIV response over the past 15 years.

But it was also a stark wake-up call. Despite the tangible results – which include millions of lives saved – it is increasingly clear that to achieve the goal of ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030, the world needs to take the fight several steps further.

Accelerating progress across all infectious diseases

Dr Ren Minghui, Assistant Director-General for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases

WHO

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agreed last September at the United Nations in New York, offer an ample opportunity to accelerate progress across all infectious diseases. The focus on equity, health systems strengthening, universal health coverage, and multi-sectoral action will transform the way we tackle these diseases.

The SDGs build on the momentum generated during the Millennium Development Goals era, and on lessons learned during the first 15 years of this century. And they recognize that while the global response has significantly reduced the infectious disease burden and saved over 50 million lives, much more needs to be done.

In 2000, who would have thought that by 2015 the world could get 17 million people in low- and middle-income countries on antiretroviral treatment, reduce malaria mortality rates by 60% and cut tuberculosis (TB) deaths by 47%? Who would have predicted that, within the space of 15 years, it could bring down the number of guinea worm infections from over 75 000 to just 22? But it did.

What we have to do now is maintain our resolve and further intensify our efforts.

“More than anything, the next 5 years should be about creating solid foundations for ending the infectious disease epidemics everywhere. This is not a moment to lift our foot off the accelerator. These diseases are known for returning with a vengeance, if we ever slow down.”

Dr Ren Minghui, WHO Assistant Director-General for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases

Infectious diseases continue to have far-reaching impacts on people’s lives. In some of the poorest countries of the world, they continue to devastate economies and cripple health systems. Progress remains uneven and millions are not being reached with prevention measures and treatment.

From the outset, the fight against infectious diseases has been dogged by social, legal and economic barriers, and funding gaps have been significant. These are a major reason why HIV, TB, malaria, viral hepatitis and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) still kill more than 4 million people every year.

Globally, 480 000 people develop multi-drug resistant TB each year, and drug resistance is starting to complicate the fight against HIV and malaria, as well. A coordinated effort to tackle this challenge – under the umbrella of the WHO global action plan on antimicrobial resistance – will be critical to success.

Global strategies on infectious diseases

To help countries deliver on their pledge to ‘end the epidemics’ by 2030, the World Health Assembly has adopted global strategies on HIV, TB, and malaria. This year, it passed the world’s first-ever global hepatitis strategy and set the first global hepatitis targets. Since 2012, a WHO roadmap has been available to guide global efforts on NTDs which affect over a billion people.

The strategies are backed up by a set of evidence-based guidance documents to help countries design and implement their own plans. They emphasize opportunities to maximize the impact of prevention, treatment and care services, and to mitigate the impact of biological challenges, such as drug and insecticide resistance, and climate change.

At the same time, WHO is working to help countries move closer to universal health coverage, by ensuring that all people have access to the health services they need, without being thrown into poverty as a result.

As well as establishing robust health financing systems, this means building up a qualified workforce and investing in efforts to improve the quality of treatments, diagnostics and prevention tools. It means assuring adequate supplies of affordable, safe and effective health products and putting an end to stock-outs. And it means joining up the dots: a greater integration of services, as we are already seeing in many places.

More than anything, the next 5 years should be about creating solid foundations for ending the infectious disease epidemics everywhere. This is not a moment to lift our foot off the accelerator. These diseases are known for returning with a vengeance, if we ever slow down.

This post was authored by Dr. Ren Mingui (WHO Assistant Director-General for HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases) originally appeared as a commentary on the World Health Organisation website on 17th August 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/2016/Endemic-infectious-diseases-next-15-years/en/

Under the

Under the

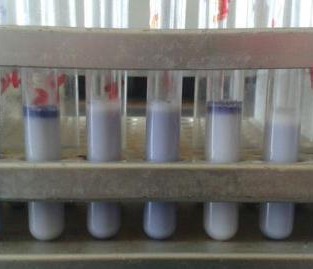

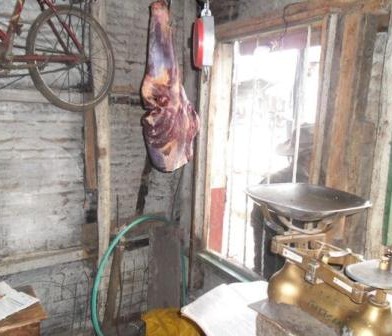

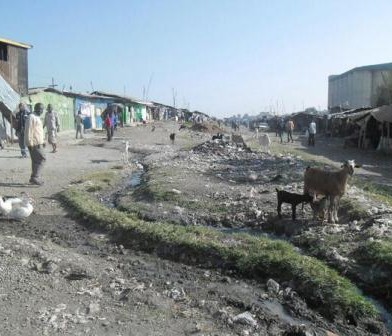

Human, food and environmental data are among the wide range of data collected within the

Human, food and environmental data are among the wide range of data collected within the

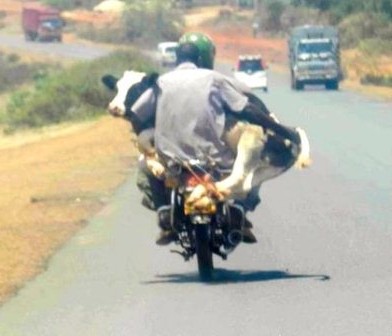

As we approach the final quarter of the

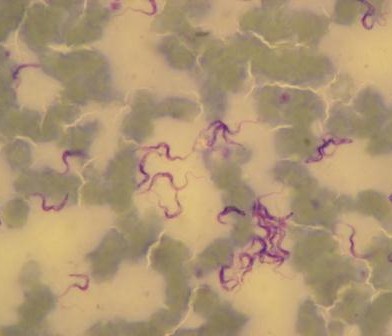

As we approach the final quarter of the  disease ecologists, and additional samples provide an important resource for future epidemiological work. We next check the rodent traps – we use live-capture Sherman traps which are set throughout the house, livestock-keeping facilities and the household compound. Any rodents that we catch are transported back to the lab at ILRI, where they are humanely euthanized and subjected to a post-mortem examination (PME). This procedure is used to permit the collection of fresh faeces and organ samples which are stored frozen and in formalin. The latter ensures that tissues from these animals are preserved for histopathological interpretation, should the need arise in the future. As dusk settles over Nairobi, the sampling team heads back to the house to trap bats.

disease ecologists, and additional samples provide an important resource for future epidemiological work. We next check the rodent traps – we use live-capture Sherman traps which are set throughout the house, livestock-keeping facilities and the household compound. Any rodents that we catch are transported back to the lab at ILRI, where they are humanely euthanized and subjected to a post-mortem examination (PME). This procedure is used to permit the collection of fresh faeces and organ samples which are stored frozen and in formalin. The latter ensures that tissues from these animals are preserved for histopathological interpretation, should the need arise in the future. As dusk settles over Nairobi, the sampling team heads back to the house to trap bats. unharmed. When we encounter a bird or bat roost, we use tarpaulins spread underneath the roost in order to collect pooled faecal samples representative of the individual animals using the roost.

unharmed. When we encounter a bird or bat roost, we use tarpaulins spread underneath the roost in order to collect pooled faecal samples representative of the individual animals using the roost.

Article by

Article by

You must be logged in to post a comment.