The four members of the organizing committee of the One Health for the Real World Symposium and key players in the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium: (left to right), James Wood, University of Cambridge; Andrew Cunningham, Zoological Society of London; Ian Scoones, Institute of Development Studies; and Melissa Leach, Institute of Development Studies (this and all photos on this page except the ILRI photo directly below of Annie Cook are via Flickr/ Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium).

This post is written by Annie Cook, post-doctoral scientist, ILRI

One Health can be defined as the collaborative effort of several disciplines

to attain optimal health for people, animals and our environment.

The 27 speakers at a recent One Health for the Real World Symposium: Zoonoses, Ecosystems and Wellbeingmake up a (very) respectable ‘who’s who’ in the world of One Health, which includes all those working to unite the knowledge, practices and approaches of medical, veterinary and environmental sciences for the healthy wellbeing of all three.

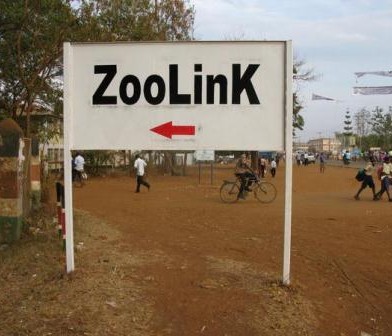

The symposium was held at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) 17–18 Mar 2016 and organized by ZSL and a three-year project called the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium (DDDAC). The symposium marked the culmination, and ending, of the consortium.

Twenty organizations, including the Africa-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), made up the Dynamic Drivers consortium, which from 2012 to 2015 coordinated research exploring the relations among African ecosystems and zoonotic diseases—those transmitted between animals and people—that impinge on ecosystem, human and animal wellbeing.

The ‘real world’ in the symposium’s title reflected the ambition of the consortium members to share their three years of research results not only with each other but also with the policymakers and practitioners who could make a real difference in advancing the One Health agenda.

Indeed, Melissa Leach, chair of the DDDAC and director of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex, stressed in her welcome address the importance of linking science and research to policy and practice. ‘Politics is key to moving forward on difficult One Health issues’, she said.

Leach was followed by Wellcome Trust director Jeremy Farrar, whose keynote presentation raised the bar even higher: ‘If we make the right choices, make the right connections, we can change the course of history’, Farrar argued. He also stressed that tackling today’s growing global health threats called not only for strong leadership but also for exceptional trust in such sensitive areas as disease surveillance and response, governance and data sharing.

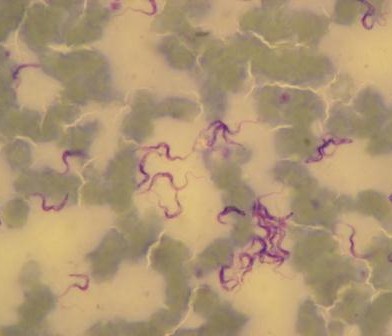

One of the ‘right choices’ and ‘right connections’ that Farrar mentioned must be greater public understanding of, investment in, and policy focus on the transmission to humans of diseases originating in wild and domesticated animals. A remarkable 61% of all human pathogens, and 75% of new human pathogens such as those causing bird flu and HIV/AIDS, originate in animals. This ‘zoonotic’ thread (and threat), while often overlooked and under-appreciated in similar fora, happily was apparent in each of the following five major themes raised in the symposium’s subsequent keynotes and discussions.

View Farrar’s slide presentation: The real world: One Health—Zoonoses, ecosystems and wellbeing

1 Anthropogenic drivers of disease, including changes in land-use and human behaviour

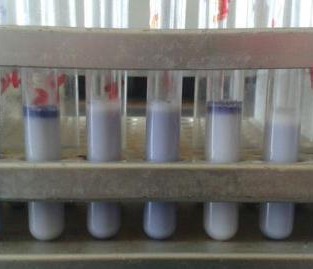

Bernard Bett, a veterinary epidemiologist at ILRI, presented a case study of the DDDAC program that investigated the effects of irrigation on levels of the virus causing Rift Valley fever in human blood serum. Rift Valley fever is an acute, fever-causing viral disease of domesticated animals, such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels, with ability to infect and cause illness, sometimes fatal, in humans. Bett’s study found that those living in irrigated areas had higher levels of antibodies to the pathogen than those in pastoralist areas. Preliminary results indicate sheep and goats from irrigated and riverine areas had higher rates of exposure to the Rift Valley fever virus than those from pastoral areas. But because the results were statistically not significant, further research is required to determine the role of irrigation in acute human and animal infections with Rift Valley fever.

View Bett’s slide presentations: Irrigation and the risk of Rift Valley fever transmission—A case study from Kenyaand A mathematical model for Rift Valley fever transmission dynamics

View Bett’s media interview: The hidden dangers of irrigation, SciDevNet, 22 Mar 2016

View Bett’s impact case stories: One Health working brings widespread Rift Valley fever out of the shadows andProtecting livestock and securing livelihoods during threats of epidemic

2 The need for an interdisciplinary approach to One Health research

Jakob Zinsstag, of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, emphasized the added value of integrating human and animal health approaches rather than allowing them to work in isolation. The knock-on effects of considering One Health problems in isolation was also stressed by David Waltner-Toews, of Veterinarians without Borders-Canada, who stated that ‘emerging infectious diseases are symptoms of related wicked problems embedded in complex social-ecological feedbacks’. A novel approach to considering One Health was raised by Jan Slingenbergh, a consulting animal health specialist formerly with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, who proposed a ‘global risk analysis framework’ similar to that developed to address global warming.

View Zinsstag’s slide presentation: Understanding zoonotic impacts: the added value from One Health approaches

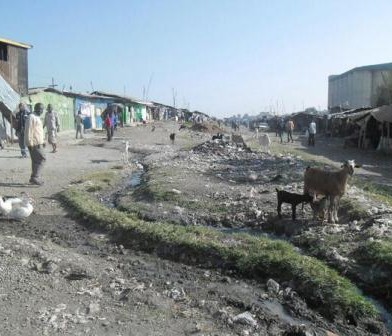

3 The relationship between One Health and poverty

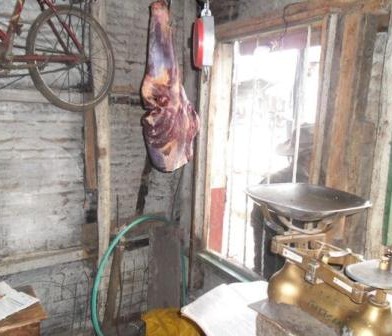

The keynote address for this theme was given by ILRI veterinary epidemiologist and food safety specialist Delia Grace, who presented an in-depth review of the relationships among ecosystems, poverty and zoonoses. ‘Human sickness is a major cause of falling into and remaining in poverty and much of this is related to agriculture’, she said. This was further emphasized by Jo Sharp, of the University of Glasgow, in her presentation highlighting the catastrophic effects of ill health. Grace reported that misdiagnosis and underreporting were two big challenges in tackling emerging infectious diseases. She warned that ‘hurried responses to zoonoses are often anti-poor, causing more harm’. And she underlined how effective control can be: ‘Every dollar invested in brucellosis control returns six dollars in reduced burden’.

View Grace’s slide presentation: The economics of One Health

4 Should One Health research focus on emerging or endemic diseases?

Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, highlighted drivers of emerging disease, such as land conversion, intensification of livestock production and wildlife trade, and the costs of controlling pandemic threats. He noted a false dichotomy between neglected tropical diseases and emerging diseases: ‘Emerging diseases become endemic diseases’, he said. Sarah Cleaveland, of the University of Glasgow, stressed the complementarities and gains ‘from adopting shared approaches to emerging and endemic diseases’. Endemic zoonoses and emerging zoonoses often have similar drivers, she said, but emerging zoonoses get more publicity. ‘Effective health systems for neglected endemic zoonoses will also help control emerging diseases.’

View Daszak’s slide presentation: Pre-empting the emergence of zoonoses by understanding their socio-ecology

5 The need to incorporate different perspectives into One Health research

Bassirou Bonfoh, director general of the Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire, stressed the need to incorporate ‘different viewpoints, knowledge and expertise’ when designing health systems. Several presentations reiterated the need to incorporate the voices of different people; a commonly repeated phrase at the symposium was ‘whose knowledge counts?’ Hayley Macgregor, of the Institute of Development Studies, highlighted a danger in research: ‘People’s cultural logics or social practices are readily cast in negative terms’.

View Bonfoh’s slide presentation: Motivation, culture and health in a socio-ecological system in Africa

In the final keynote, Charlotte Watts, chief scientific advisor at the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), argued that One Health approaches can be very effective for decision-makers facing a crisis. As an example, she listed the diverse options available for controlling the ongoing Zika outbreak using ecosystem, medical and veterinary scientific knowledge and technologies.

The final panel discussion, with representatives from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), summarized the themes of the symposium’s discussions and introduced further relevant issues concerning biodiversity, conservation and animal welfare.

A highlight of the symposium were lively one-minute ‘flash talks’ by poster presenters. The 28 posters presented covered diverse topics, including many with a livestock focus, such as the following.

Kathryn Berger, of the University of Cambridge, presented a ‘Global atlas of animal influenza’ that can be used for surveillance and control programs.

Birungi Doreen, of Makerere University, pointed out that research on possible Ebola virus disease in pigs in Uganda had some negative impacts on the pork value chain in that country and required sensitizing stakeholders to reduce any harm such research could cause.

Natascha Meunier, of the Royal Veterinary College, showed that diseases transmitted from wildlife to cattle most likely occurred via indirect routes, particularly vector-borne disease transmissions.

Robin Wiess, of the University College London, reminded us that zoonosis is a two-ways street: Humans can be a source of infectious disease in animals. ‘Don’t forget the “anthroponoses!”’.

The symposium also included the launch of a book, One Health—Science, Politics and Zoonotic Disease in Africa, edited by Kevin Bardosh, which offers ‘a much-needed political economy analysis of zoonoses research and policy’.

The closing statement Melissa Leach stressed that One Health is not always comfortable integration. ‘As a social scientist, I see that One Health is about solving puzzles, dispelling bullshit, learning new things and making the future different’. Indeed, a recurring theme throughout the symposium was the need for a new generation of ‘multidisciplinary professionals’.

And there was a final plea from Ian Scoones, of the STEPS Centre and the Future Agricultures Consortium: ‘Let’s not make a new One Health discipline—yet another silo!’

The symposium was organized by the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium (DDDAC) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) with support from the Royal Society. The DDDAC is multidisciplinary research consortium funded by the UK’s Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation (ESPA) program, which works to ensure that developing-country ecosystems are sustainably managed to alleviate poverty alleviation as well as to support inclusive and sustainable growth.

Go here to find out more about ILRI research on zoonotic diseases and here for past ILRI news stories on One Health.

About the Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium

The Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium was an international, multidisciplinary research programme. From 2012 to 2016 it explored the relationships between ecosystems, zoonoses, health and wellbeing, focusing on four emerging or re-emerging zoonotic diseases in four diverse African ecosystems: henipavirus infection in Ghana, Rift Valley fever in Kenya, Lassa fever in Sierra Leone, and trypanosomiasis in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Its innovative, holistic approach married the natural and social sciences to build an evidence base which is now informing global and national policy seeking effective, integrated One Health approaches to control and check disease outbreaks.

Authored by J

Authored by J

Authored by

Authored by

You must be logged in to post a comment.