One World-One Health at the RSTMH Biennial Meeting, autumn 2016

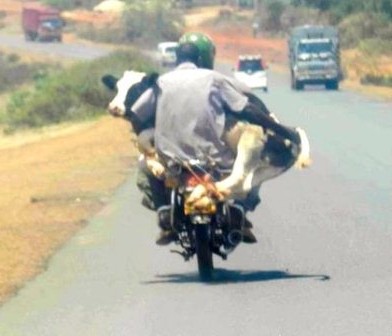

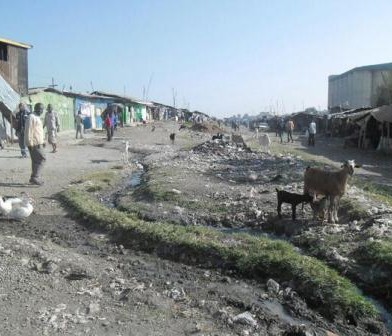

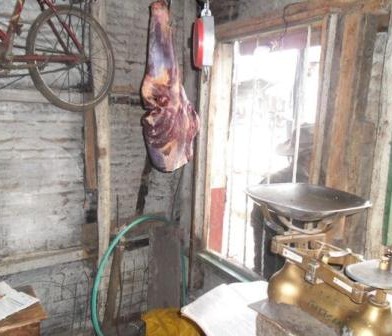

“There are fears that Africa’s next major modern disease crisis will emerge from its cities. Like Ebola, it may well originate from animals”. So writes Eric Fèvre from Nairobi in his conversation “Urban Zoo”

This intimate association between human and animal health underpins what is known as the One Health agenda, recognised by both the WHO (World Health Organisation) and the OIE (World Animal Health Organisation). And it’s not only in Africa that urgency applies but throughout the world, particularly in developing regions where surveillance systems are at their weakest and pandemic spread is highly likely.

Against this backdrop, the RSTMH is showing great insight in focussing attention on the need to bring together medical and veterinary health delivery systems and expertise under the headline of “One World-One Health” (OW-OH). Lord Soulsby, the veterinary parasitologist and long-time proponent of OW-OH, celebrated his 90th birthday last year. Hence it was entirely fitting for the RSTMH, as part of its Biennial Meeting in autumn last year, to kick off an afternoon programme dedicated to OW-OH by hosting the inaugural Soulsby Lecture followed by a series of presentations by world authorities in their field.

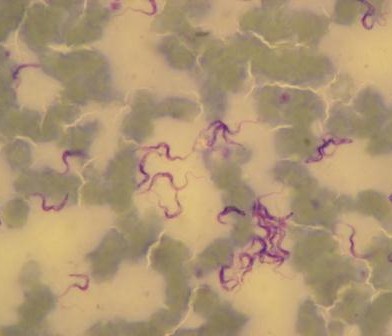

Of great importance was the decision to focus the programme on the challenges and opportunities for human and animal health delivery systems to collaborate and take a more holistic systems-based approach. The message that “the collaborative whole is greater than the sum of the parts” was obvious throughout, from David Heymann’s opening message early in the conference (new challenges in the ‘last mile’ of disease elimination caused by animal reservoirs) to Sandy Trees’ illumination of how veterinary research into onchocerciasis in cattle has given new insight into river blindness in humans; from Sarah Cleaveland’s demonstration of how mass rabies vaccination of dogs is both feasible and cost-effective in eliminating the disease in people, to Eric Fèvre’s plea for disease surveillance systems to consider the human-animal interface in relation to the “Urban Zoo”.

I was particularly drawn to the case made by Bernadette Abela-Ridder that many rural communities in the least developed countries live in close proximity to their animals. This means that eliminating zoonotic diseases is critically important to their own health as well as the health of their animals. Furthermore the financial well-being of these communities is also dependent on the health and well-being of their animals. And Esther Schelling illustrated the importance of generating community engagement and trust to deliver such integrated programmes.

Many health delivery programmes reside in silos directed only towards human populations – either intentionally (“this funding is only for human health benefit”) or through lack of information (“we didn’t realise the relationship with animal health”). By pooling resources, significant cost savings can be made. And the benefits to each sector will be clearly demonstrable by attributing costs carefully.

So for me, there are two massively important take-home messages to be drawn from all this wisdom.

Firstly that eradication of human disease will often be frustrated by failing to appreciate the parallel situation in animal health. This may be due to lack of awareness of animal reservoirs of infection or to failure to incorporate essential veterinary experience and resources. The sooner veterinary and medical scientists and practitioners work more effectively together to contribute to the challenges they all face, the better the world will be.

And secondly, and equally importantly, resources available to achieve disease elimination are necessarily limited and, to be effective, require local involvement. The sustainability of such local involvement may weaken just at the time when it is most needed – the ‘last mile’ when the big gains have already been achieved and the final small but essential gains require relentless and absolute commitment. At such a time, that same local involvement could be sustained by broadening their remit to include animal health matters; same skills – different patient. However the silos of project funding seem often to not support this happening.

By acting on these take-home messages, both human and animal welfare will benefit and opportunities for disease elimination in both populations will become more realistic.

This article originally appeared on the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene website available at (here). Authored by Judy MacArthur Clark

You must be logged in to post a comment.