Antigenic diversity in the African trypanosomes Trypanosoma congolense and Trypanosoma vivax

Antigenic diversity in the African trypanosomes Trypanosoma congolense and Trypanosoma vivax

Blog entry authored by Sara Silva Pereira, PhD student University of Liverpool.

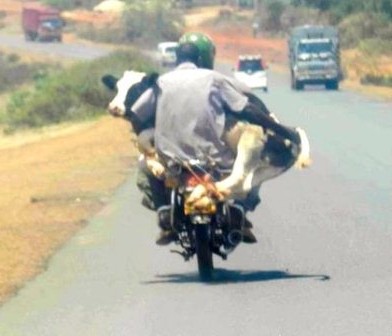

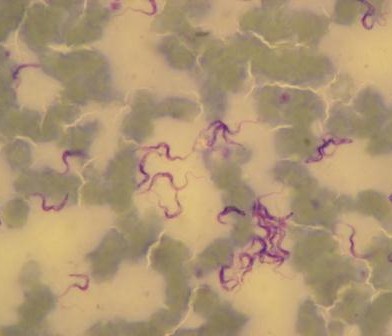

Trypanosomes are extracellular blood parasites, transmitted by the bite of tsetse flies and cause nagana, a wasting disease severely compromising both animal health and livestock productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nagana remains a challenge mainly due to the process of antigenic variation, employed by the para-site for immune evasion.

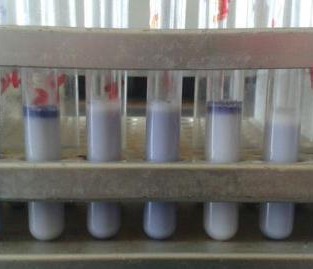

Blood sampling

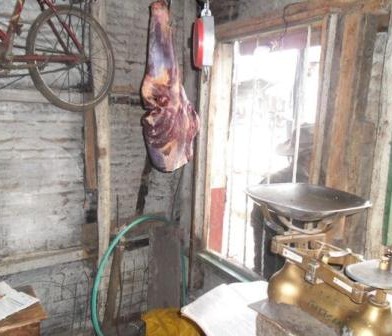

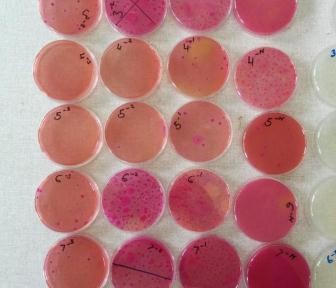

I came to Busia to conduct a longitudinal experiment on natural cattle infections of T. congolense to better understand the process of antigenic switching. With the help of a local veterinary surgeon, we screened cattle across for trypanosomes using thin blood smears and high centrifugation technique and followed the infection in positive animals for a month, after which the animals were treated.

The collected materials will be subject to DNA and RNA sequencing and Mass Spectometry to characterise the genetic repertoire of the parasites and the antigens expressed over time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.