Co PI’s Letter: Planning and Policy Team

Co PI’s Letter: Planning and Policy Team

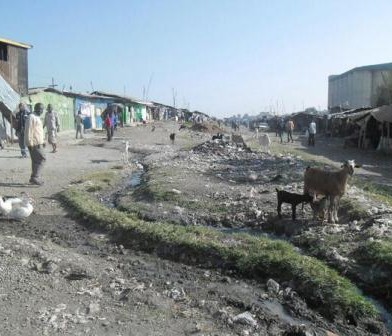

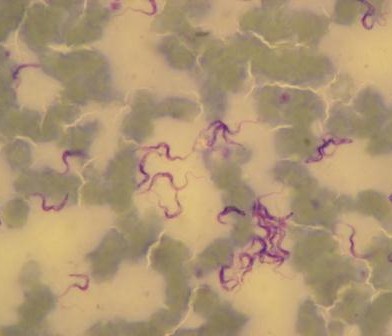

The Planning and Policy Team’s work focuses on the socioeconomic and environmental conditions that contribute to the diversity of microbial exposure of urban residents. It is estimated that 60 percent of Nairobi’s residents live in informal settlements, where inadequate housing, insufficient basic infrastructure and services and widespread livestock keeping translate into severe environmental hazards. Understanding how this affects local residents’ exposure to microbial diversity is key in formulating and implementing appropriate policies.

The Planning and Policy Team’s work focuses on the socioeconomic and environmental conditions that contribute to the diversity of microbial exposure of urban residents. It is estimated that 60 percent of Nairobi’s residents live in informal settlements, where inadequate housing, insufficient basic infrastructure and services and widespread livestock keeping translate into severe environmental hazards. Understanding how this affects local residents’ exposure to microbial diversity is key in formulating and implementing appropriate policies.

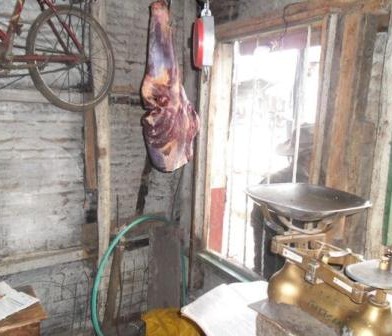

Much has happened since the last letter from the Team in April. We have continued to support the work of the Kenyan Federation of the Urban Poor, Muungano wa Wanavijiji, thanks also to additional funding from the UK Department for International Development. Building on the piloting of innovative participatory methodologies, researchers decided to focus more on food street vendors, for several reasons. The first is the central role of food vendors in providing cheap food to residents of informal settlements who often do not have space to cook and store food, nor time to prepare meals at the end of long working days. Street vendors also play an important role in the social life of the settlements, by congregating along the main roads until late at night and in this way increasing security for those residents, especially women, returning home after dark. Because of its flexible working hours and minimal need for starting capital, selling food, either raw or cooked, is also one of the main sources of income for women, especially those responsible for young children and sick relatives.

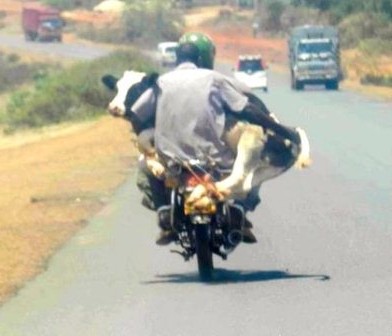

But while they may not be harassed by the authorities like their colleagues working in the ‘formal’ part of the city, street vendors within informal settlements face several challenges which can also generate health risks to their customers. These include food contamination due to proximity to solid waste dumps, open air sewers and roaming

livestock; limited access to water – in many cases only available at high prices from private vendors –to wash food, hands and utensils thoroughly; inadequate public lighting and high levels of insecurity that can prevent sellers, especially women, from selling after dark. Such issues require holistic interventions that address both socio-economic and environmental conditions. Documenting the challenges and setting up vendors’ associations that can establish a dialogue with local authorities to develop appropriate interventions are key steps, as described in a new working paper: Cooking up a storm: Community-led mapping and advocacy with food vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements .

Another step has been the joint organisation with our Urban Zoo partners APHRC and ILRI of a series of ‘training of trainers’ on food safety and handling for street vendors and Muungano members, the first of which took place in July. Collaboration between grassroots organisations and scientists in the project enriches our understanding, and helps

identify ways in which research can inform and stimulate action.

Dr. Cecilia Tacoli is a Principal researcher, Human Settlements Group and a team leader, rural-urban development at IIED.

You must be logged in to post a comment.