Overview

African camels could hold important clues to controlling the potential spread of a respiratory disease transmitted by the animals.

For many years African camels have lived with the disease and the risk of it spreading to humans is still low. But more research is necessary to understand the disease better. This is even more important given the confirmation that the chains of transmission of the human Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection originated from contact with camels. MERS was first recognised in 2012.

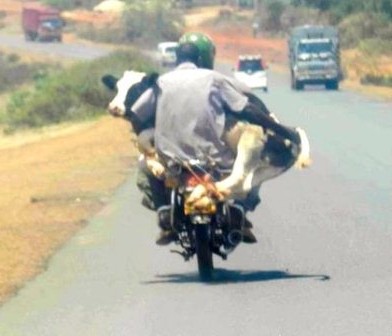

Camels are an extremely important source of livelihood, nutrition and income in Africa. They are especially common in arid and semi-arid areas of the continent, particularly in East Africa. But having these animals around may not be risk-free for humans.

However there have been no human case of MERS diagnosed in Africa. This could be because of limited clinical or epidemiological surveillance for the virus where infections have gone unrecognised. It could also be because there is simply no zoonotic, human infective virus circulating in sub-Saharan Africa, or indeed because risk factors for transmission differ in the two regions.

MERS from an African perspective

Looking at Africa, what do we know about the disease and the potential risk of transmission?

The disease usually affects patients who are in some way immune-compromised or suffering from other conditions like diabetes, lung and liver disease.

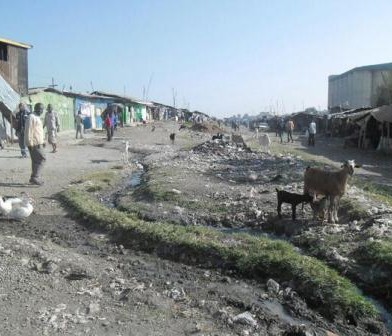

Livestock dependent people in the Horn of Africa region who suffer from malnutrition are potentially at risk of contracting the disease. The case fatality rate of MERS is high, at around 37%. Outbreaks in other parts of the world like South Korea have been linked to individuals originally acquiring infections from chains of transmission originating in the Middle East and travelling.

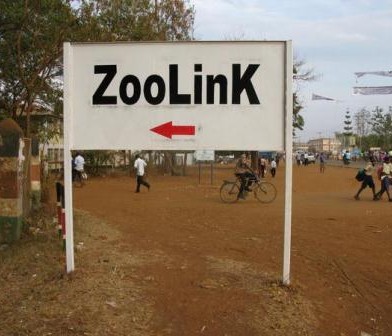

In October the Centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development at the Intergovernmental Authority on Development and the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation co-hosted a scientific and policy meeting to discuss the MERS virus. The aim was to improve the understanding of this pathogen and its implications to the Horn of Africa region.

The meeting was prompted by the likely role of the dromedary camel as a reservoir of infection for MERS-CoV, and the high density of and trade importance of camels in the Horn of Africa region. The region supports more than 60% of the world’s population of single humped camels.

There are two types of camels worldwide. The dromedary camel is found in Africa and the Middle East; and the Bactrian Camel, found in Asia.

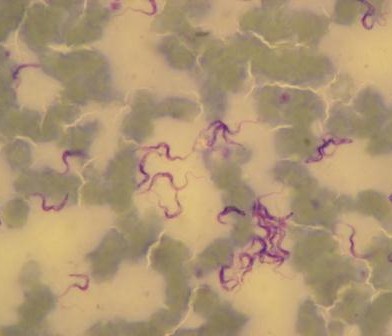

The virus in camels

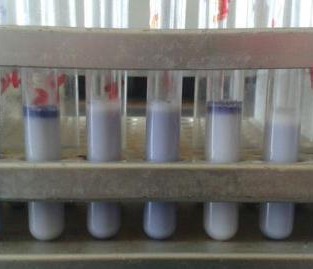

Studies in Kenya and elsewhere show that, despite its recent identification as a human pathogen, MERS has been circulating for many years over wide geographical areas. Camel sera collected as far back as 1983 shows high rates of seroconversion to the virus. This means that the animals have been infected, probably by a transient respiratory disease, and recovered.

MERS in camels, it seems, is much like being infected by the common cold. Some populations of camels in Kenya (which has the third largest camel population in East Africa) tested recently show seroconversion rates of 47%. This is a widespread virus that is actively circulating and has been around for a long time.

A crucial question in understanding the disease is establishing what the human risk is when the virus circulates so freely in the reservoir host. It is vital to learn whether dromedary camels in Africa harbour the same MERS-CoV as detected in the Arabian Peninsula. If so, or if not, is the epidemiology of the virus similar?

This is despite the high seroconversion rates, as the virus appears to affect camels early in life – possibly before they have weaned – and self cure within a matter of weeks.

Mapping trade routes and understanding the population structure of African camels better with their population density will also be key foresight information should large scale disease control interventions ever be necessary.

More research is key

The appearance of a new disease in a widely distributed reservoir host is a worrying prospect. It does however seem that camels in Africa have been living with MERS-CoV for a long time. While the risk of spill over to humans from this population cannot yet be discounted, it appears to be, for now, a low risk.

Even though the Middle East has seen outbreaks of a virus with zoonotic potential, it might be that the mutations required to make this possible have only evolved recently and in that locality. The newly acquired zoonotic potential may not be widespread. To better understand if this is the case, active efforts are underway in sub-Saharan Africa to isolate the virus itself and genetically type it.

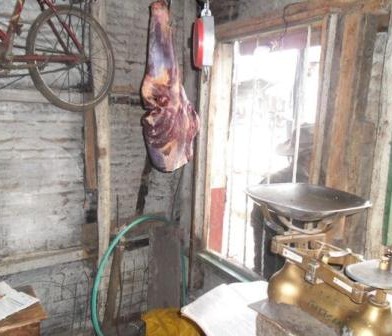

In conjunction with genetic studies of the virus, work is also underway to determine whether people, and particularly those at high potential risk such as camel herders and slaughterhouse workers, have also seroconverted to the virus. This would demonstrate that human infections have taken place.

Part of the effort to do this involves building local diagnostic capacity in Africa, to ensure that such at-risk populations can be monitored through time and increase the speed of a public health response if required. As with many diseases, a diagnostic test that could be used in the field would be ideal for such monitoring.

For long term preparation, a key research priority is to understand the continental distribution and diversity of camel populations themselves. The camel is very much under-researched, compared to other livestock such as cattle, goats and sheep, despite its importance to rural livelihoods in many areas.

This gives the livestock and health communities the opportunity to study and better understand this virus, ideally working on a joint agenda that shares knowledge. An example of this is the One Health philosophy between sectors that benefits all.

Dr Joerg Jores of the International Livestock Research Institute featured as a co-author on the piece.

This article was authored by Eric Fevre (Professor of Veterinary Infectious Diseases, University of Liverpool) and originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article by Clicking here

You must be logged in to post a comment.