Promoting Food Access and Livelihoods for Vendors in Informal Settlements

Promoting Food Access and Livelihoods for Vendors in Informal Settlements

Kenya’s urban poor federation Muungano wa Wanavijiji is working with food vendors in informal settlements to reveal their challenges and explore how to promote food security. Muungano is a member of Slum Dwellers International (SDI), a network that aims to improve shelter, services, and government responsiveness to the urban poor. The ongoing project is complement-ing other Urban Zoo activities, as well as building upon Muungano’s past experience with grassroots data-collection and advo-cacy. Working alongside Muungano are community residents, pro-poor financial analysts at Akiba Mashinani Trust (Muungano’s financial wing), and researchers at University College London and UC Berkeley.

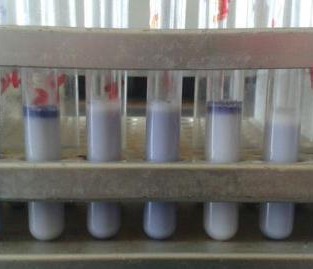

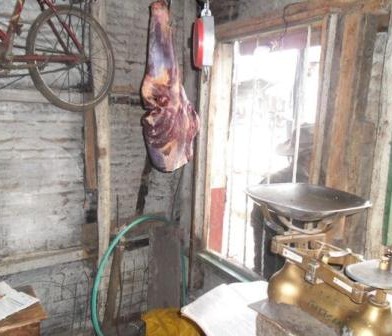

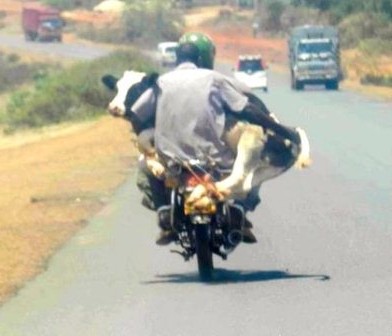

This action-research project is utilizing participatory methods to understand vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani. Vendors sell a variety of items in these settlements such as fresh produce; meat, fish, and eggs; cooked and uncooked foods; beverages; and snacks. A mobile phone application is capturing vendors’ demographic and business profile, while base-maps and balloon-mapping (low-cost aerial photography with balloons and a simple camera) are generating detailed spatial data on their locations. Finally, focus group discussions (FGDs) are delving into traders’ constraints, coping strategies, and priorities for change.

This action-research project is utilizing participatory methods to understand vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani. Vendors sell a variety of items in these settlements such as fresh produce; meat, fish, and eggs; cooked and uncooked foods; beverages; and snacks. A mobile phone application is capturing vendors’ demographic and business profile, while base-maps and balloon-mapping (low-cost aerial photography with balloons and a simple camera) are generating detailed spatial data on their locations. Finally, focus group discussions (FGDs) are delving into traders’ constraints, coping strategies, and priorities for change.

These vendors are poorly organised and frequently overlooked or stigmatised by policy-makers, yet vending is a vital source of affordable, accessible foods and a key income-generating activity. Customers may appreciate the convenience and their personal relations with traders; food vending is also a widespread livelihood strategy, particularly for female traders seek-ing to combine work with childcare. As a female vendor explained in a Viwandani FGD, “I’ll be doing my work and also doing the house chores and also look after my kids…But if you are outside [the settlement], sometimes you have to look for someone to take care of your kids and sometimes you don’t have that money.”

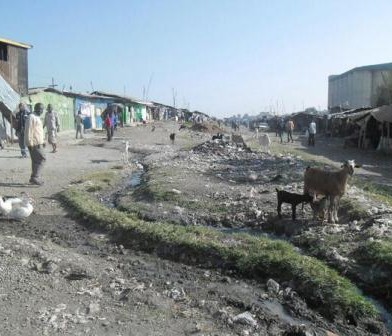

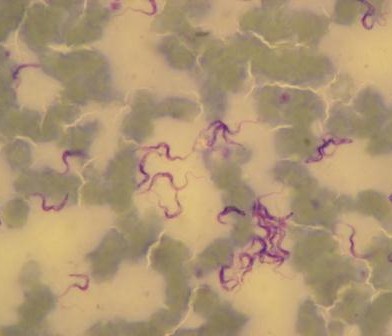

However, vendors often face multiple challenges in their settlements like overflowing drains, minimal water and sanitation, uncollected rubbish, and elevated insecurity. In turn, widespread hazards and poor infrastructure or services can threaten food security by jeopardising vendors’ livelihoods and customers’ access to food. But the project’s maps and FGDs are uncovering these concerns and, moreover, a Food Vendors’ Association (FVA) has been established to increase their collective strength, amplify their voices, and advocate for much-needed interventions in the future.

However, vendors often face multiple challenges in their settlements like overflowing drains, minimal water and sanitation, uncollected rubbish, and elevated insecurity. In turn, widespread hazards and poor infrastructure or services can threaten food security by jeopardising vendors’ livelihoods and customers’ access to food. But the project’s maps and FGDs are uncovering these concerns and, moreover, a Food Vendors’ Association (FVA) has been established to increase their collective strength, amplify their voices, and advocate for much-needed interventions in the future.

This action-research project is utilizing participatory methods to understand vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani, with support from APHRC and ILRI team members from the Urban Zoonoses project.

This article has been written by the Muungano team

You must be logged in to post a comment.