Animal diseases make up 60 per cent of all human pathogens and have a significant impact on poverty. Yet for many years, the worst diseases were sorely neglected by the international community. Eric Fevre describes how this turned around, and what researchers are now doing to tackle it.

Animal diseases make up 60 per cent of all human pathogens and have a significant impact on poverty. Yet for many years, the worst diseases were sorely neglected by the international community. Eric Fevre describes how this turned around, and what researchers are now doing to tackle it.

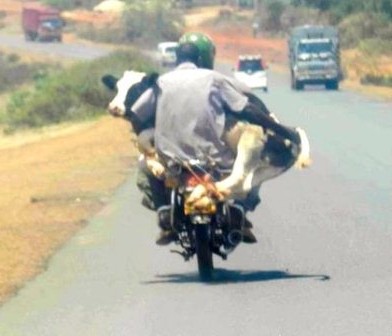

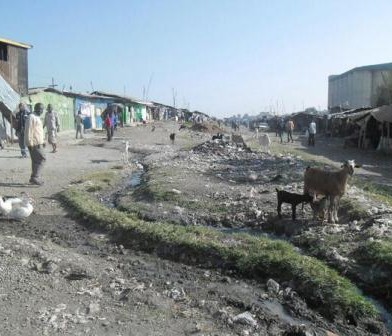

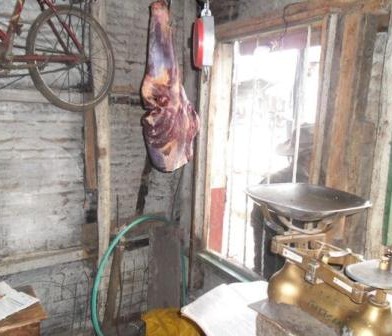

In the far west of rural Kenya, close to the border with Uganda, livestock keepers struggle with poverty, food security, and a considerable burden of both animal and human disease. Ninety-five percent of the population of this region, sandwiched between Lake Victoria and Mt Elgon, are smallholders – growers of crops and keepers and small herds of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens. The animals people keep are the backbone of their domestic stability – providing essential food and nutrition, but also serve as an investment, cashed in when the need for funds arises, which is often to pay for heathcare or school fees. And it is for these reasons that diseases linked to animals are devastating for such communities.

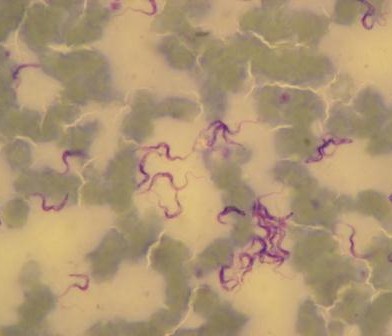

The ‘Neglected Zoonotic Diseases’ (NZDs) include rabies, zoonotic Human African Trypanosomiasis, brucellosis, anthrax, q-fever, Rift Valley Fever, cysticercosis, leptospirosis, bovine tuberculosis, leishmaniasis and several others. They are defined as a group of endemic, lingering diseases, originating from an animal source, mostly affecting poor communities in slums and remote rural areas of the developing world.

NZDs are grossly under-reported so their impact is almost invisible in national statistics. As they have little effect on trade or international travel they are paid very limited attention by national governments or the international community, despite the profound effect on those living in endemic areas.

Zoonoses constitute approximately 60 per cent of all human pathogens, and some – such as avian influenza – receive tremendous amounts of international attention and funding. Others tend to cause chronic pathologies or long-lasting outbreaks, in areas such as Western Kenya, where the levels of poverty and the lack of political voice by those affected means that they do not get the attention that they probably deserve.

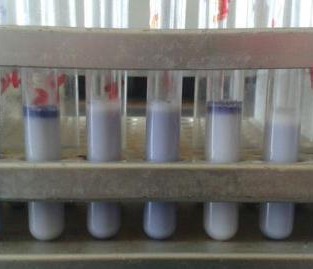

We say probably deserve because in some instances, there simply are no data, in either the human or the livestock populations, to suggest how important the diseases really are. Sometimes data are collected locally (e.g. in hospitals) but is never communicated up the chain to give a national picture. At other times, the fevers and body aches that are a characteristic sign of many of these pathogens get diagnosed as malaria. Reports show that for sleeping sickness patients end up attending different clinics 7–10 times before a proper diagnosis is made, by which point they are much sicker. This is because diagnostic tools, when they exist, don’t reach the treatment centres caring for these communities. And even when a correct diagnosis is made, drugs are poorly available to treat the infection. So from a larger scale perspective, not having data about the disease in an area means little further effort is put in by overstretched public services to follow-up investigations.

And zoonotic diseases don’t just affect health. They impact on the production and health of livestock, inflicting a ‘dual burden’: less milk, less meat, less traction power, less money. All this is bad news for a poor farmer whose family and livestock may also be infected at the same time (maybe even infecting each other). To compound this, effective control and prevention often needs to be targeted at the animal reservoir rather than the people, while the budgets for such diseases (if there is a budget at all) rests with the human health services. Human health protection thus must include or even depend on the veterinary sector, which is itself relatively underfunded (budgets for human health promotion usually end up in Ministries of Health). Thus, these problems often fall between the cracks of responsibility.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been spearheading an international effort to raise the profile of a number of zoonotic diseases over the last 5-8 years. The term NZDs was coined in late 2004, inspired by the success of campaigning around Neglected Tropical Diseases. In 2005, the WHO initiated a series of advocacy conferences associating NZDs control with poverty alleviation, the outputs of which are captured in a series of reports (see references below).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been spearheading an international effort to raise the profile of a number of zoonotic diseases over the last 5-8 years. The term NZDs was coined in late 2004, inspired by the success of campaigning around Neglected Tropical Diseases. In 2005, the WHO initiated a series of advocacy conferences associating NZDs control with poverty alleviation, the outputs of which are captured in a series of reports (see references below).

Bringing NZDs onto the international health agenda was essential, but a balance had to be struck with other new, emerging diseases of animal origin with the potential to spread across borders and affect worldwide trade and travel. You’ll be familiar with some of them: avian influenza, SARS, BSE. These new diseases have been mobilising much of the attention and resources going to zoonoses research over the past 20 years, even though, overall, their public health impact remains small compared to the accumulated annual burden of the major NZDs.

In January this year, several stakeholders agreed a roadmap toward control or elimination of several Neglected Tropical Diseases. It is highly significant that three of the NZDs (porcine cysticercosis, cystic Echinococcosis and dog rabies) were among those on this expanded list, suggesting that efforts to raise the profile of zoonotic infections are bearing fruit. The Director General of WHO (Margaret Chan) has acknowledged the importance of these diseases and veterinary public health as one of the five public-health strategies for the prevention and control of NTDs.

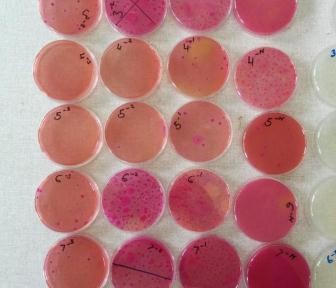

Meanwhile, researchers like myself are tackling zoonotic diseases from a scientific standpoint. Our Wellcome Trust-funded ‘People, Animals and their Zoonoses’ project, based at the University of Edinburgh and hosted in Kenya by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), is addressing the lack of scientific understanding on the distribution, scale, impact and basic biology of many zoonotic infections.

The upside of the dual burden of NZDs is that efforts to understand and control these pathogens also have a ‘double whammy’ positive effect: first, on the livestock and their production, and second on human health. Those WHO meetings in 2006 recommended a series of advocacy and awareness raising steps (some of which have clearly been successful, given the inclusion of three NZDs in the NTD list). Importantly, it also proposed that targeting pastoral communities, remote sedentary rural populations in Africa and Asia and marginalised urban livestock producers (all groups most affected by NZDs) was necessary, to:

- Undertake rigorous, small-scale field-based epidemiological studies to gather basic information for the design of control programmes.

- Assess the burden borne by individuals affected by NZDs.

- Assess the cost of the disease to livestock production.

- Study risk factors in both people and animals with a view to successfully targeting at-risk groups for high priority interventions.

- Investigate methods for quantifying the rate of underreporting of these diseases in humans.

- Improve, develop and assess new disease control, prevention and monitoring tools (including diagnostic tools) adapted to the conditions prevailing in developing countries.

- Undertake these studies in multidisciplinary teams, involving both human and animal health expertise – i.e. working towards the concept of “One Health.”.

In July 2001, an interagency meeting organised by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) classified NZDs into packages to attract donors: cysticercosis, echinococcosis, fascioliasis and other food-borne trematodes, dog mediated-rabies and bacterial zoonoses. It was conservatively estimated that $20 million annually would be required for research and control efforts for these packages.

The job of raising the profile of NZDs is underway. Important commitments have been made to tackling them and the international community is certainly more aware than it was. But there are still significant gaps in our understanding of their biology and the burden. For researchers like us, we realise there is still a long way to go.

Featured here:http://blog.wellcome.ac.uk/2012/02/21/the-neglected-ties-binding-human-and-animal-health/

The Zoonotic and Emerging Disease group studies a range of epidemiological issues revolving around the domestic livestock, wildlife and human interface

You must be logged in to post a comment.