Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) – What do we know?

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) – What do we know?

In the summer of 2012 in Saudi Arabia a strange corona virus infection was isolated from a patient with acute pneumonia and renal failure. Subsequently, a series of laboratory diagnostics divulged a novel coronavirus later known as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS COV).

Following the virus identification, a new case was reported from a Qatar patient in the UK and a cluster of hospital cases were reported among health workers in Zarqa, Jordan. There was ineffable fear that the world was fronting another pandemic after the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

As of June 3rd 2015, there have been 1,179 confirmed cases of MERS and 442 fatalities in 25 nations representing a case fatality rate of 37.49%. South Korea is the latest country to report two deaths and 35 cases in the largest outbreak outside Saudi Arabia. The vast majority of the South Korean cases have been acquired from hospitals with the fast spread attributed to the fact that family members often stay with patients in their hospital rooms.

MERS-CoV infection in humans occurs either as outbreaks as witnessed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia where 255 confirmed cases were reported in four months or as isolated cases. The infection’s clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic to a very severe pneumonia with the acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock and multi-organ failure ensuing in death.

Serological studies have confirmed camels have antibodies against the virus. In addition, virus detection by reverse transcription PCR and sequencing has confirmed that these antibodies are likely to be caused by infection with a similar virus strains that infect humans, although a formal confirmation of the role of camels in the epidemiology of the virus is still elusive. Transmission has largely remained human to human with a few isolated primary cases having a histo-ry of contact with camels, suggesting that they are a source of human infection.

A number of questions regarding the dis-ease have remained difficult to answer:

- What is the reservoir of the virus, and are there multiple animal species that may form a reservoir community? If yes, which ones?

- The infection has predominantly affect-ed older people. Is this related to abil-ity to fight infection, or is it exposure related?

- The evolutionary background of MERS-CoV is unclear; antibodies against the virus were found in Kenyan camels during a period spanning from 1992 to 2013. This implies that the virus exist-ed in camels long before it was identified and before it jumped to the human population. Nevertheless, the appearance of human cases in the last few years might indicate some kind of mutation of virus that allows it be become human infective. If this is the case, could it spread rapidly though the human population? If this mutation has occurred, has it occurred in multiple locations simultaneously?

- What is the risk of human infection from camel populations outside the Middle East (eg in Kenya)

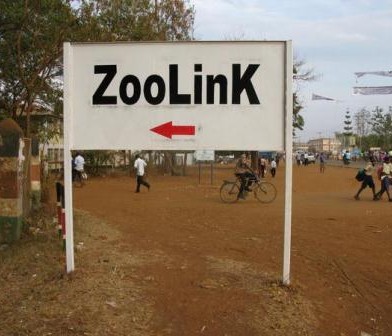

In collaboration with a number of partners, including St Louis Zoo, the Mpala Research Center and the Erasmus Medical University, we are investigating elements of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV in camels in Kenya to help answer some of the above questions.

In collaboration with a number of partners, including St Louis Zoo, the Mpala Research Center and the Erasmus Medical University, we are investigating elements of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV in camels in Kenya to help answer some of the above questions.

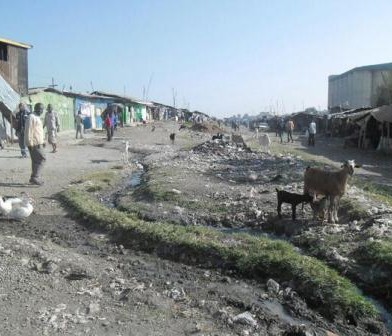

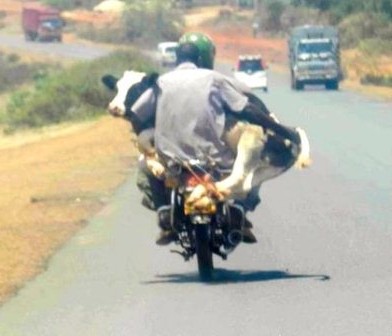

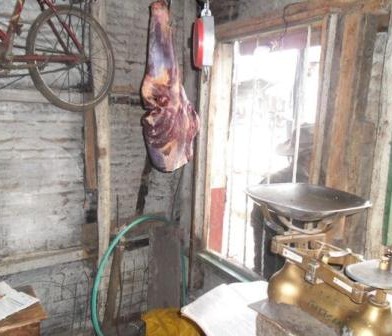

These studies are an extension of the Urban Zoo project’s activities investigating camel value chains in Kenya and Nairobi.

Article by Dishon Muloi (dshnmuloi@gmail.com)

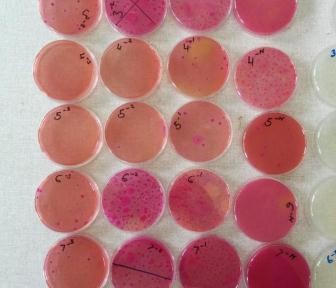

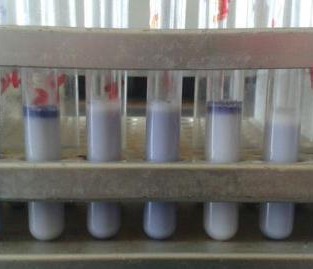

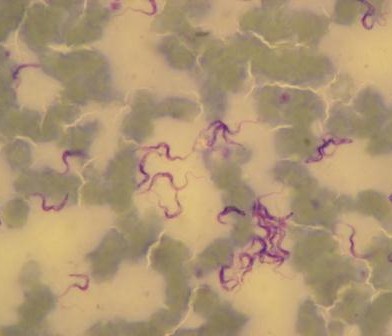

The power of next generation sequencing is allowing us to gain a more detailed understanding than ever before about how bacteria spread. I am hugely excited to be a part of the Urban Zoonoses project, which will generate a vast amount of bacterial isolates along with meta-data at an unprecedented level of detail.We will be performing whole genome sequence analysis of bacterial samples collected through many strands of the Urban Zoonoses project, from humans, livestock, food, wildlife and the environment. I will use state-of-the art methods for integrating the bacterial genetic sequence data with information about the time, loca-tion and host from which the bacteria were sampled. By combining epidemiological and demographic infor-mation with the genetic data, we will be able to under-stand the E. coli diversity within Nairobi, and how this differs across socioeconomic groups, in different housing types and in relation to livestock keeping practices.

The power of next generation sequencing is allowing us to gain a more detailed understanding than ever before about how bacteria spread. I am hugely excited to be a part of the Urban Zoonoses project, which will generate a vast amount of bacterial isolates along with meta-data at an unprecedented level of detail.We will be performing whole genome sequence analysis of bacterial samples collected through many strands of the Urban Zoonoses project, from humans, livestock, food, wildlife and the environment. I will use state-of-the art methods for integrating the bacterial genetic sequence data with information about the time, loca-tion and host from which the bacteria were sampled. By combining epidemiological and demographic infor-mation with the genetic data, we will be able to under-stand the E. coli diversity within Nairobi, and how this differs across socioeconomic groups, in different housing types and in relation to livestock keeping practices.

You must be logged in to post a comment.