‘A Day in the Life of the People, Animals and their Zoonoses (PAZ) Project’, is series of blog articles by several members of ILRI staff working on the PAZ project based in Busia. These staff members, share their first hand experiences, challenges, and highlights of the project, in this post George Omondi Acharry, a laboratory technician talks about Fascioliasis in western Kenya.

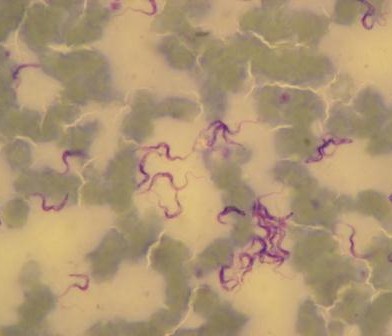

Fascioliasis is a disease mainly of domestic ruminants (and also affects humans although no human case so far has been reported in Kenya) caused by liver fluke parasites Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica. Although the former Fasciola species is more common in the tropics and causes serious losses in cattle, sheep and goats and thus posing a major threat to resource poor farmers, Fasciola hepatica has also been reported to occur in high altitude areas of Kenya. In such areas, the two Fasciola species occur side by side.

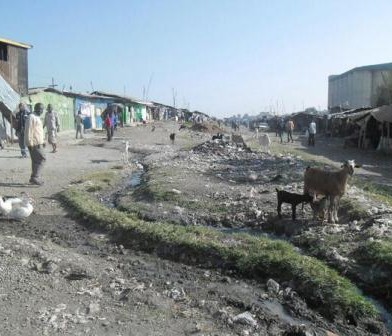

The disease is fairly widely spread across Kenya save for variations in infection risk because of the heterogeneity in agro-ecological zones (AEZs) and production systems. The People, Animals and their Zoonoses (PAZ) project area, Busia and other areas such as the highlands, Rift Valley, Lake Victoria basin and Coastal strip that experience enhanced rainfall throughout the year tends to favour the survival of the intermediate host, the Lymnaeid snail Lymnae natalensis. Fascioliasis. Prevalence is higher in these areas compared to dry areas particularly the northern frontier districts and lower eastern Kenya that receive less rainfall.

life cycle of fasciola hepatica and fasciola gigantica

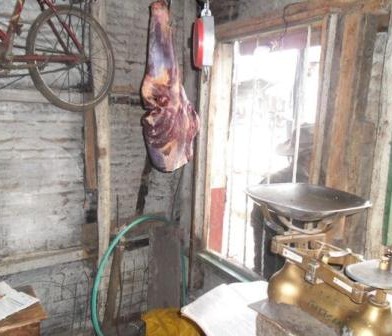

Fascioliasis has also been identified as a major cause of liver condemnations in slaughtered animals throughout Kenya. Livers infected with Fasciola parasites are either partially (trim off affected sections) or totally condemned. Although it is difficult to quantify the economic losses due to fascioliasis, farmers in Busia and other parts of the country lose an estimate of £7 million Kenyan meat every year. The high condemnation of Fasciola infested livers of slaughtered cattle throughout Kenya (10% to 60% livers per annum), calls for urgent attention in order to forestall further losses. Comparatively, the losses in sheep and goats is moderately lower as it ranges between 3% to 15%. The variation between cattle, sheep and goats losses could be due to the fact that majority of sheep and goats infected with fascioliasis tend to die before reaching slaughter age as above explained.

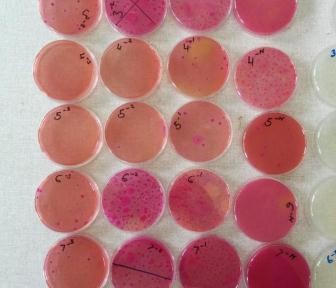

For a long time, sedimentation technique has been relied on in diagnosing fascioliasis. However, other newer techniques have been developed such Kato-katz that is more sensitive in detecting Fasciola eggs, Schistosoma bovis and other helminth eggs. The sedimentation technique is used both by KARI and ILRI in the PAZ project but kato-katz has also been adopted by the latter. From our studies we have been able to show that fascioliasis is most prevalent in swampy areas.

Although effective control of fascioliasis should be targeted at the parasite or the intermediate host (snail) level, the latter method is by far the most popular. Chemical molluscides such as copper sulphate and N-trityl morpholine though quite effective in controlling snail hosts have limited application due to the associated environmental implications and their effect on non-target acquatic organisms. In the late 1980s, KARI validated the use of Eucalyptus globosus leaves as a snail control strategy. Though this strategy was very effective, its application is almost impractical owing to the hydrological effect of Eucalyptus tree species cause to the environment. This means that the current and future fascioliasis control will largely be dependent on anthelmintics. This method of fascioliasis control though popular, has certain disadvantages including the prohibitively high cost of anthelmintic drugs, increased risk of consuming meat and milk containing drug residues and the risk of drug resistance. In our study the infected animals are normally treated using effective conventional anti-fasciola drugs.

About the author

George Omondi is a laboratory technician working with the PAZ- ILRI project on secondment from KARI. In his past research career, he has been working in the field of veterinary helminthology and he has been involved in many such research projects in Kenya. Currently he has developed an interest in epidemiology of fascioliasis in cattle.

The Zoonotic and Emerging Disease group studies a range of epidemiological issues revolving around the domestic livestock, wildlife and human interface

You must be logged in to post a comment.